Australia. Gallipoli.

How many beaches were the British responsible for? How many was the US responsible for?

I think the mark goes sailing over your head with obtuse, over-generalizations like that. You tell us: what was the British “objective” at Dunkirk? What was the German one?

Bonjour à tous.

I just happened to look on here in order to impress someone by using RS’s smart quote by Montesquieu, and found myself reading some of the posts on this thread.

Regarding: the smiley-faced Tommy, I wouldn’t disagree with much of what has been stated. However, I would ad (if it hasn’t been said already) that not all of the British troops had had contact with the advancing German forces when Gort ordered the retreat to Dunkirk. Also, many had weathered the worst winter in Europe for many years and were, perhaps, relieved to be heading home. After all, the British were not in love with the idea of being under the command of the French.

Arguably, those queuing on the mole would have been quite relieved at the prospect of getting on the next ship. Add to this the banter which most soldiers in most armies turn to when things aren’t running according to plan, and you have occasion for smiling. Furthermore, one might argue that he was smiling at the prospect of getting his leg over (I’ll translate that for Nick: getting laid) when he gets back home.

Finally, I must thank the wind from the East (with a polite fart) for affording you all the opportunity to rally-round-the-flag, so to speak, and support your poor beleaguered British colleagues.

A+

32B

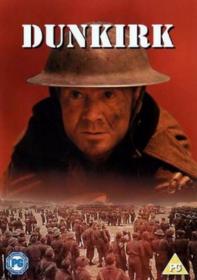

p.s. My sister hated the film. She said it made them look as if they were running away.

I can’t think of any argument to contradict your sister’s assessment.

Dunkirk is probably unique in having such a large body of defeated troops massed for successful evacuation. Greece was a bit similar, but less well organised, and some of those troops went on to fight shortly after in Crete where they punished the invading Germans before being defeated again.

Alas, it didn’t happen in Singapore or the Philippines where the British Commonwealth and US lost substantial forces which, had they been evacuated with anything remotely like the success at Dunkirk, possibly would have impeded Japan’s subsequent south-eastern thrust and certainly aided the Allies’ subsequent north-western offensive against Japan.

I say ‘possibly’ because the fact remains that the Malayan defence and more so the Philippines defence tied up Japanese troops and logistics and prevented them being used further east, which in turn ensured that any intention to invade Australia and the eventual Operation FS to move towards Guadalcanal etc had time for the growth of Allied forces in Australia and elsewhere to resist that thrust.

If Singapore and or the Philippines had been evacuated similarly to Dunkirk with huge numbers of Allied troops, with at best some small arms and occasional machine guns, the only useful destination was Australia where neither the Australians nor the early stages of the American build up in Australia had any prospect of having the logistical resources to make any offensive use of them until early to mid-1943, by which time the Japanese had been repulsed on Guadalcanal and eastern New Guinea. Those evacuated troops would more likely have been a logistical burden until they could be re-trained and re-equipped. Nonetheless, those extra troops would have been very useful from mid-1943 onwards, whether as offensive troops or garrison troops in Australia to release other forces for offensive action.

So, with due respect to your sister’s accurate opinion, it still holds true that it’s not a bad thing to run away and live to fight another day.

The loss of men with the fall of Singapore and the Philippines was a tragic waste. Both allied armies got themselves bottled-up with no place to go and no hope of relief. It has, of course, led to much finger-pointing ever since. The Japanese were ready, the Allies weren’t. As RS has pointed out elsewhere, the British were busy fighting for survival in Europe. The Mediterranean was, arguably, the best/only way of taking the war back to the Axis forces given the limited resources available to the British after Dunkirk. There was also the battle for the Atlantic to consider, which was incredibly important. Arguably more so than the Mediterranean. Plus there was the strategic air campaign over Germany. Much was being done by a small nation punching above its, then, weight.

I like to think of the retreat to Dunkirk as a withdrawal. Never easy when the enemy is in hot pursuit. The BEF hadn’t been broken when Gort ordered the retreat (the main thrust of the German assault was elsewhere), so I wouldn’t be tempted to describe it as running away or a rout. Of course, the operation was hampered by the numbers of refugees on the roads, exacerbated by the Luftwaffe. So much so, that many units were forced to abandon their heavy equipment in order to make any progress.

The large scale operations in which Allied forces retreated in other theatres mainly came about by direct enemy action. Greece, Crete, Philippines, Malaya… Of course, another massive retreat which led to a reasonably safe haven, and a base from which to strike back, was that from Burma to India (when discussing the fight back through Burma, and other theatres, and the subject of manpower, it would be remiss to ignore the enormous contribution of the Indian Army).

Interesting concept, retreating and then striking back. Wellington did it for several years in the Peninsular Campaign, again, mainly on account of limited resources. With Manstein, in the East, it virtually became a doctrine and was continued by NATO during the last Cold War.

I generally liked the film. That being said, I do have major problems with its flaws. the lack of details and the simplistic distillation of everything down to a couple of small air battles and a comparatively small number of Brits waiting on the beach with the French sitting in sandbag castles at the town’s edge. Dunkirk was a major battle with fierce, desperate fighting by both sides. Yet the combat is limited to desultory rifle fire and a group of Tommies being wiped out in the beginning. I don’t really think that is in any way an accurate portrayal. But no doubt there was a desperate sense of getting out and going home that pervaded. But the Germans are reduced to scary, off-camera monsters you hardly see and the Brits always running and this doesn’t show accurately that Dunkirk wasn’t a town as much as it was a vast, slowly collapsing pocket of piss and fire…

I think your term “bottled up” defines the difference between Dunkirk and, on the other hand, Singapore and the Philippines. The British and US / Filipino forces had no way of escaping from the containments to which they were forced and retreated to by the Japanese advance, but the British at Dunkirk did, courtesy of the proximity of Britain across the relatively narrow English Channel and the ability of the RN to protect the evacuation.

There’s a reason it’s called the English Channel and not the French Channel, because the English / British and the RN have controlled it for centuries. Against that, one wonders whether the Germans couldn’t have done more damage to the Dunkirk evacuation from the air on the narrow Channel. Perhaps not, with countless small boats being countless targets for a limited number of German planes.

Unlike Dunkirk, the British at Singapore and the Americans / Filipinos in the Philippines lacked the transport to take them across vast distances to safety in, briefly, the NEI before they fell and then, or previously directly, to Australia.

It’s interesting to contrast the French belief in fortifications which failed to deal with an unexpectedly successful German advance around the fortifications with Singapore and the Philippines. In Singapore the high command refused to erect fortifications in good time as Japan advanced through Malaya because it didn’t want to damage morale, and thus ensured the early collapse of the ‘impregnable fortress’ by leaving its approaches open to successful Japanese but quite basic amphibious assaults. In the Philippines the ultimate defence was long based on ‘last redoubt’ fortifications in Bataan and especially Corregidor which were the ultimate “bottle up” of land forces, with no prospect of relief from sea or air and insufficient logistics to sustain the defenders, ably assisted by MacArthur’s idiotic positioning and loss of a major supply dump in the path of the Japanese advance as the Japanese were running out supplies.

Admittedly, the Philippines defence, like the Singapore theory, assumed that land forces would hold out until rescued by the vast resources of the relevant nation’s navy in a few months, so it wasn’t entirely the land forces’ fault that they lost when their respective navies failed to turn up.

I’d suggest that the primary problem was that the largely green Commonwealth ground forces were often led by inexperienced and at times complacent and arrogant officers from platoon level upwards to battalion and even brigade level, while the Japanese were often battle hardened troops from China.

There were many other issues which rendered the Malayan / Singapore defence doomed from the outset, most of which were beyond the control of the British commander at the time. He was pretty much handed a poisoned chalice with the only choice being how quickly or slowly he drank it.

In the Philippines, there was MacArthur. He was the arrogant, incompetent poisoned chalice gifted to the doomed Filipinos.

Agree entirely.

Until the US involvement began to have some effect around mid 1942, Germany had in preceding years overrun pretty much all of western Europe and was advancing rapidly into eastern Europe, as well as being drawn by the incompetent Italians into North Africa. When one considers the punishment the Germans delivered to the Soviets and the land and air forces employed by the Germans in that campaign from mid-1941 it is apparent that Germany should have been able to swat the British land and air forces anywhere without much trouble in mid-1941. The fact is that the Germans didn’t, while the British defeated the air assault in the Battle of Britain and pressed on in the Battle of the Atlantic while pressing on with various failures and successes in, what for Germany were a bit of a sideshow, in North Africa, Greece and Crete, along with naval successes in the Med and elsewhere.

Unlike the Soviets, Britain never faced the full might of massed German land and air forces from mid-1941, but it was still the only nation (with its Commonwealth) fighting the Germans and, until the invasion of the USSR, always risked the full might of those overwhelming forces being applied to Britain.

Although the British forces in the field were always vastly less than the total forces the Germans could have used against them in the field, the fact remains that the British (and Commonwealth) forces held the Germans to a draw or defeat after Dunkirk, on land, sea and in the air.

It can be argued that, for whatever reason, Germany didn’t apply all its force to Britain so Britain didn’t do all that well. The Battle of Britain, where Germany pitted its air might against Britain in anticipation of an invasion, contradicts that argument. And the consistent ultimate failure of Germany against British and Commonwealth forces reinforces that contradiction.

I was responding to your sister’s description of it as ‘running away’.

I agree that it is more accurately described as a withdrawal. And an orderly one at that.

It certainly wasn’t a rout.

I might be overlooking something, but I can’t think of a true and major rout involving British or Commonwealth troops in WWII. For that matter, I can’t think of a true and major rout involving US troops in WWII (the Kasserine Pass went close in segments, but overall it wasn’t a rout of US troops) and , unlike the massive true rout of US troops in Korea a few years after WWII, again with perhaps often poorly trained occupation troops who were as green as the British Commonwealth troops in Malaya and the American / Filipino troops in the Philippines in WWII and, I would suggest, even much more badly led by many of the American Army commanders from battalion level upwards in the early rout in Korea, but not by the equivalent USMC commanders who, like the Marines at all levels, generally did a comparatively brilliant job as the battlefield collapsed around them.

As far as Dunkirk, it was certainly a brilliant ad hoc operation conducted in the clouds of the fog of war where both sides were shocked by the rapidity and success of the German advance. The Allies were shocked by their incompetence against a strategic coup de main encirclement. The Germans were befuddled by the lack of real time communications with the forward units causing understandable angst in OKW, and fears that a yet undiscovered mechanized Anglo-French reaction force may still exist. Those fears were stoked by the desperate Allied attempts to sever the Panzer Corridor, not least of which was -but also not limited to- The Battle of Arris.

The Fall of the Philippines was a shock and terrible for morale, but it was hardly a catastrophic loss in terms of numbers as about 15,000 Americans servicemen were lost to death and capture. I think that it bears mentioning the high numbers captured were mostly Filipinos often exaggerating the loss in terms of numbers. I haven’t read about Warm Plan Orange in a while, but I wonder if RS* has an opinion on a hypothetical Japanese operation by-passing the Philippines by launching only limited attacks to reduced naval and air assets and leaving more troops and other assets to conducted operations elsewhere. Would this have been feasible? Even preferable to leaving a large occupation force there?

The Battle of Kasserine Pass was a (perhaps necessary) embarrassing bloody nose for American forces, and perhaps a minor tactical rout. But it was contained by the Leadership of General Harmon, who took over the command of the battle, reorganizing both US and British assets and employing a skillful use of artillery to limit the damage. Also, the Afrikakorp didn’t have the strength nor supplies to conduct a decisive penetration in depth. So in the end, it relieved the US Army of one of its worst commanders in history since at least The War of 1812, that “coward sonofabitch!” Gen. Fridenhall, who was too busy hiding in his elaborate bunker over a hundred miles from the battle. And it led to reforms of command and control and better leadership obviously with Patton taking command after Harmon turned it down.

On the whole, I think I preferred this one.

I think it was feasible for Japan to leave America out of its southern advance and take only British and Dutch assets, in the hope that American isolationism would not result in any American response against Japan.

Against that, the Pacific War was in part a contest for control of the Pacific that America and Japan had seen coming for years, but it was also a contest for control of China where Japan and the West, primarily America and Britain, both wanted to exploit Chinese resources as they had for decades to the detriment of the Chinese people. It was evident to Japan from US support for Chennault’s Flying Tigers in China that the US was prepared, albeit behind the veil of a ‘volunteer’ US force with many more fighters and bombers than any truly volunteer civilian force could muster, that the US was likely to take at least some sort of military and or naval action against Japan if Japan struck south and jeopardised American assets in the Philippines. Add to this that the US was the prime mover in the oil embargoes that provoked Japan to strike and it’s not hard to see that the US was seen as the major enemy and threat to Japan’s southern ambitions, with Britain bogged down in North Africa and the Netherlands government in exile in Britain.

Regardless of those aspects motivating Japan to fear American retaliation if it moved south into Malaya and the NEI, the strategic problem for Japan was that the Philippines sat astride the sea routes between the NEI and Japan, so America could frustrate exploitation of the NEI oil which Japan desperately needed.

Once Japan had resolved to take Malaya and the NEI, it considered that it didn’t have any option but to take out the Philippines to ensure its ability to exploit its new resources in oil, rubber and tin, among other things.

There is also the issue of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. This is often regarded as a smokescreen for Japan inserting itself as a replacement colonial power for the Western powers it wanted to displace (which is pretty much what it did, as it had done in Korea decades earlier as part of its imperial ambitions), but if one looks at Japanese thought and debate in the decade or two leading up to the Pacific War there was a genuine desire in many quarters to overthrow the Western colonialists. Admittedly, so far as the Philippines was concerned this was a rather weak argument for Japan in 1941 as the US had resolved in the mid-1930s to grant the Philippines independence in 1945.

Having decided to go to war, Japan had to attack Pearl Harbor to disable the US Pacific Fleet, in part to prevent it relieving the Philippines.

Against that background, Nick, I think it was probably feasible for the Japanese to bypass the Philippines.

Apart from MacArthur’s, in long war terms, relatively small and increasingly isolated air force (most of which he lost on the first day of the invasion anyway with no discernible impact on the conduct of the actual long war) and some ageing USN ships stationed in the Philippines, there was at best the prospect of short term annoyance to Japanese shipping which came within range of those forces.

The Japanese land forces tied down in the Philippines during WWII were largely occupation forces or fighting locals on land, which had no bearing on any risk to Japan’s sea lanes from the NEI and Malaya.

As it was, the ageing USN ships left the Philippines pretty quickly after the Japanese invasion. The same might well have occurred without the Japanese invasion, to preserve those ships from a perceived threat as Japan took Malaya and the NEI. But this assumes that Japan still attacked Pearl to prevent its fleet relieving the Philippines, which was the event that outraged America and Americans and ensured Japan’s defeat.

If there was no attack on the US and the Pearl Fleet wasn’t attacked in Hawaii but was deployed to protect the Philippines, it didn’t necessarily follow that US forces would attack Japanese shipping between the NEI/Malaya and Japan. Although I think that would have been inevitable as the US and Britain, and the Netherlands, were all determined that Japan would not get NEI oil.

In the end, I suspect that even if Japan had chosen to bypass the Philippines and not attack Pearl, circumstances would have forced the US to resist Japan in South East Asia to some extent. Whether that would have escalated to the real war which occurred is debatable.

Be all that as it may, I think Japan’s decision to attack Pearl and invade the Philippines was strategically necessary to give it the best chance of securing its aims.