…In this climate of clash and controversy, Britain tardily began the formation of its first modern armored division. The Germans already had four and were building more. Hobart’s fears and predictions were being realized. He was the logical man for the command, and the new secretary of war, energetic, reform-conscious Leslie Hore-Belisha, was determined that Hobart should get the vital assignment. War Office conservatives dug their toes in and treated Hore-Belisha to a bewildering exhibition of bureaucratic and professional resistance. The secretary was unable to put Hobart into the post, and recalled in later years: “In all my experience as a minister of the Crown, I never encountered such obstructionism as attended my wish to give the new armored division to Hobart.”

A cavalryman whose most recent assignment had been the training of riding instructors was proposed by the War Office for command of the new armored division. This proposal fairly characterized the uncomprehending state of British military thought on the eve of the world’s greatest war. In a compromise arrangement with the War Office, Hobart became director of military training. Hore-Belisha hoped by this stratagem that Hobart’s personal drive, enthusiasm and knowledge of armored warfare could permeate all army training.

[b]The tank genius was now deep in “enemy” territory. He was the last tank man of high rank left in an influential post. Like a loathsome infection, he was gradually walled off by the subtle processes of the War Office organism, while pressure mounted to expel him entirely from that august body. Hore-Belisha was continually urged to dismiss Hobart.

The Munich crisis provided the right emotional climate and an excuse to get rid of him completely. He was bundled on a Cairo-bound aircraft, assigned to raise and train Britain’s second modern armored division. With Hobo’s removal to the Nile delta, tank thinking was exterminated in Whitehall [Britain’s Foreign Office], and as Liddell Hart put it, “The British Army was again made safe for military conservatism.” For these decisions on the part of its highest military professionals, Britain was to pay dearly in life and prestige.[/b]

Scattered motorized and mechanized troops with obsolescent equipment were all that Hobart found in Egypt as the basis for a modern armored division. A grim enough prospect in itself, the equipment situation was overhung by a demoralizing and obstructive emotional factor. Commanding in Egypt was one of the British Army’s remaining conservative hangovers from the First World War, a soldier for whom Hobart, himself a decorated veteran of the first conflict, had never failed to express his professional contempt. The commanding general was also a socially-minded soldier. He especially detested Hobart at the personal level for his 1928 marriage, for which Hobart’s wife had gone through the divorce court.

Modern minds would regard such a procedure as little more than a fact of life. To the British Army of the period between the wars, it was a transgression sufficient to bring many threats of professional retribution on Hobart, one of them from the general who now commanded in Egypt.

Hobart’s arrival was followed by a brief and brutally unceremonious interview in the quarters of the commanding general. “I don’t know why the hell you’re here, Hobart,” he barked, “but I don’t want you.”

[b]In this poisonous atmosphere, once again virtually isolated, Hobart buckled down to build the kind of armored division of which he had always dreamed. There was virtually no communication with main HQ, no sympathy with what he was doing, no co-operation and no equipment. Hobart proved his superb qualities under these negative, antagonistic conditions by bringing off the miracle of the 7th Armoured Division.

Troops accustomed to the sleepy garrison routine of Egypt found themselves with a stern taskmaster. Rushed into the desert to train by day and by night they soon found themselves permeated by the unconquerable spirit of the tall, hawk-faced Hobart. He infused them with the same magic morale he had given to the 1st Tank Brigade, and month by month he welded the scattered units into a determined, smoothly functioning fighting division.

Taking the jerboa (desert rat) as their emblem they were soon known as the “Desert Rats.” They proved themselves Britain’s finest armored division in the whole North African campaign. Lieutenant-General Sir Richard O’Connor, commander of the Western Desert Force of 1940, called the 7th Armoured Division “the best trained division I have ever seen.”[/b]

The grim and frustrating duels of the War Office and the struggle for the armored idea slipped into the background as Hobart fulfilled himself in a man’s job. [b]When war broke out in September 1939, a deadly, hard-hitting and superbly mobile force was under his command. Lean, tanned and hard of body and mind, the 54-year-old Hobo was ready for whatever the war could bring.

Three months later, Hobart was dismissed from his command and sent into retirement.[/b]

This shocking blow came at the hands of General Sir Archibald Wavell, who decided to act on an adverse report on Hobart filed by the general who hated him and who had sworn professional retribution. Normally a man impervious to the effects of opposition or professional misfortune, Hobart was shaken to the roots of his being by his abrupt and complete dismissal.

Lady Hobart recalls the 1940 dismissal from the army as the one time in their life together that the general had shown distress over any reverse. “He was a stricken man,” she says today. “To anyone lacking his intense fortitude, the wound would have been mortal. No warning whatever was given that this blow was to fall.”

[b]General Sir Archibald Wavell, who was himself a man with a keen mobile sense, was unable in later years to explain adequately his action in dismissing Hobart. The loss of the tank genius from the desert command was to have incalculable consequences for British arms and fortunes. Liddell Hart tackled Wavell about Hobart’s dismissal personally, and made it clear to him how deplorable and damaging the whole affair had been. “Wavell’s explanation was rather lame,” says Liddell Hart.

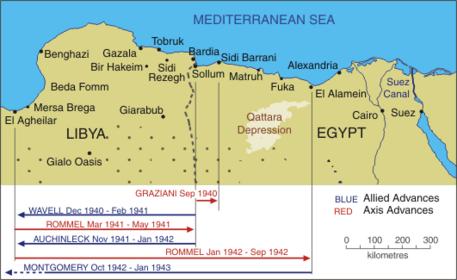

Wavell went on to win his own immortal glories by crushing the Italians with the Hobart-trained 7th Armoured Division – the only unit available and able to nullify the overwhelming Italian advantage in manpower and machines.[/b] By one of destiny’s strangest twists, Liddell Hart had compiled a list of the most promising officers in the British Army for Hore-Belisha in 1937. Only two men were singled from the multitude of British generals as likely to become great commanders – Wavell and Hobart.

The fortunes of the British Army in North Africa were left after Hobart’s dismissal in the hands of high commanders who were no more than amateurs in the handling of modern armored forces. So tight was the conservative grip on command that it was not until the latter part of 1942 that authentic tank officers even reached divisional commands. This continuing prejudice and incomprehension was reflected by the British Army’s record in the field. With an inferiority of force but with an intuitive gift for handling mobile forces, Rommel proceeded to thrash humiliatingly a succession of British generals sent against him. The troops in the field, as well as the public all over the world, began to wonder if the British had ever heard of the tank before Rommel. British troops in North Africa, repeatedly let down by their armored forces, began to look on their own tank units with considerable suspicion…