Don’t know about the level of anti-tank weapons in the Commonwealth forces.

Leccy is much better informed than me on what the Australians should have had but, as he notes, that may not be the same as what they did have.

That is further complicated by the fact that what is commonly called the 8th Division, 2nd AIF (2nd Australian Imperial Force, the first being the AIF in WWI with both being all volunteer expeditionary forces) in Malaya / Singapore was only two of the three brigades of that Division. When a formation is split up like that it doesn’t necessarily follow that every unit in it has what it’s supposed to have, even if it was available to issue to it. For example, the remaining brigade of the 8th Division was split up among various islands closer to Australia while its headquarters remained in Australia which could mean that HQ elements didn’t go into the field with the rest of the brigade. I don’t know what a 2nd AIF brigade would have had at the time as HQ elements, but building on what a company and battalion HQ would have as HQ platoon and company respectively it could be that a significant element didn’t go into the field.

As for tanks, we formed our 1st Armoured Division in 1941 with the intention of sending it to North Africa, where it would have had no impact if sent when formed as all it had was about half a dozen light Vickers tanks, and perhaps not much more effect in Malaya if sent there. But it wasn’t as it was held in Australia and built up to meet the feared Japanese invasion.

The advantage of Japanese tanks in Malaya was in getting among the Commonwealth infantry to aid the Japanese infantry’s infiltration and envelopment tactics and in bursting through road blocks or other infantry choke points. Commonwealth tanks might have stalled this in tank to tank engagements, but they probably would have been of more use in supporting Commonwealth troops against Japanese infantry as mobile pill boxes. Assuming the Japanese infantry weren’t well equipped with effective anti-tank weapons, which I doubt as their intelligence before the invasion should have told them that there was no Commonwealth armour opposing them, although if they lacked specific anti-tank weapons they probably had artillery which, as with the Australians in my last post, could be employed against tanks.

But as we couldn’t muster more than about half a dozen light tanks for our first armoured division, the absence of Australian armour in Malaya was probably inevitable. As for British armour, that’s a separate question, but I doubt that diverting scarce British armour from North Africa would have been a wise or useful move in the total scheme of things as that undoubtedly fairly meagre armour almost certainly would not have affected the result in Malaya.

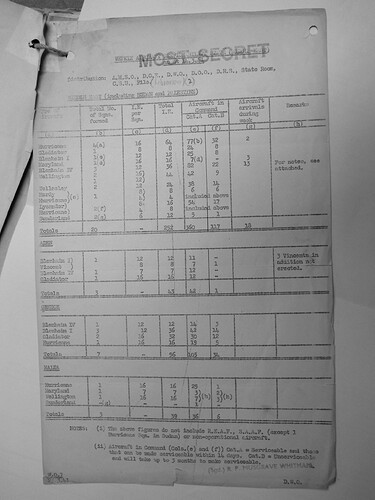

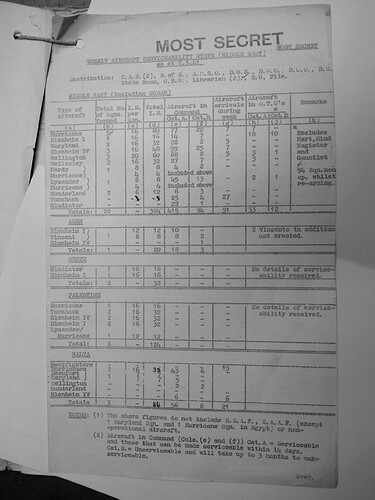

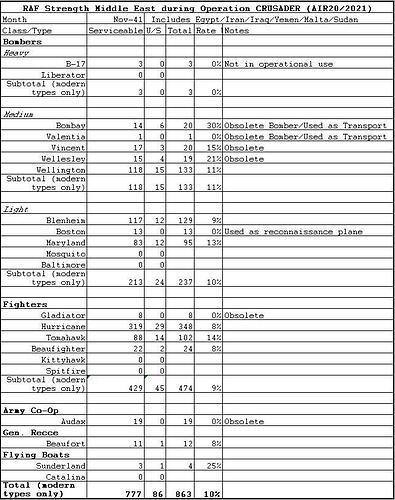

The real issue is the lack of British air cover, which if put in in the degree recommended by senior British military planners was the only thing which might, but by no means certainly would have, changed the result of the Malayan campaign.