Finally, certain graphic materials have arrived, so we can now continue with our tiny theoretical treatise about human behavior in war.

You se, my dear Mr. Ivaylo, although numerous manifestations of intragroup aggression have excited a considerable amount of attention and controversy, many specialists regard intersocietal war as the most serious manifestation of human aggressive behavior. There is a thread of continuity that runs from individual aggressiveness to organized warfare. However, when it comes to the more highly developed modern forms of military action, the link between individual biocultural responses and the plans and strategies of warleaders is rather indirect, so we cannot regard war as simply individual aggressiveness projected onto a larger screen. Nevertheless, the anthropography of so called cultivation peoples (in contrast to hunting-gathering peoples) seem warfare ridden, because numerous different human groups of various locations all seem to have in common a tendency toward internecine raiding and warfare.

Several anthropologists have carried out cross-cultural studies of warfare, attempting to generalize from large numbers of cases. Keith Otterbein, for example, has tasted a number of generalizations concerning the development of warfare habits and demonstrates the not-unexpected finding that more complex communities have more complex organization for warfare. Escalation of warfare to more serious dimensions depends, however, upon an aggressive drive which is induced by existing structure of the society, and it motivates behavior of the individual to injure the obstacle. The usual cause of human aggression is frustration, and the other is that aggression has the properties of a basic drive – being a form of human energy thet persists until its goal is reached as well as being an inborn reaction. The most important anthropological fact, however, is that the forms that aggression takes, and the situations in which it is displayed are determined largely by social influences, generally know in theory as differential reinforcement. Those influences on the other hand have almost similar pattern in completely different societies.

That is the theory. And now we shall examine those theoretical postulates in praxis. Please observe very carefully these confirmed historical examples of utterly aggressive, non-ethical and lethal behavior in war, which are connected with dissimilar systems of human societies:

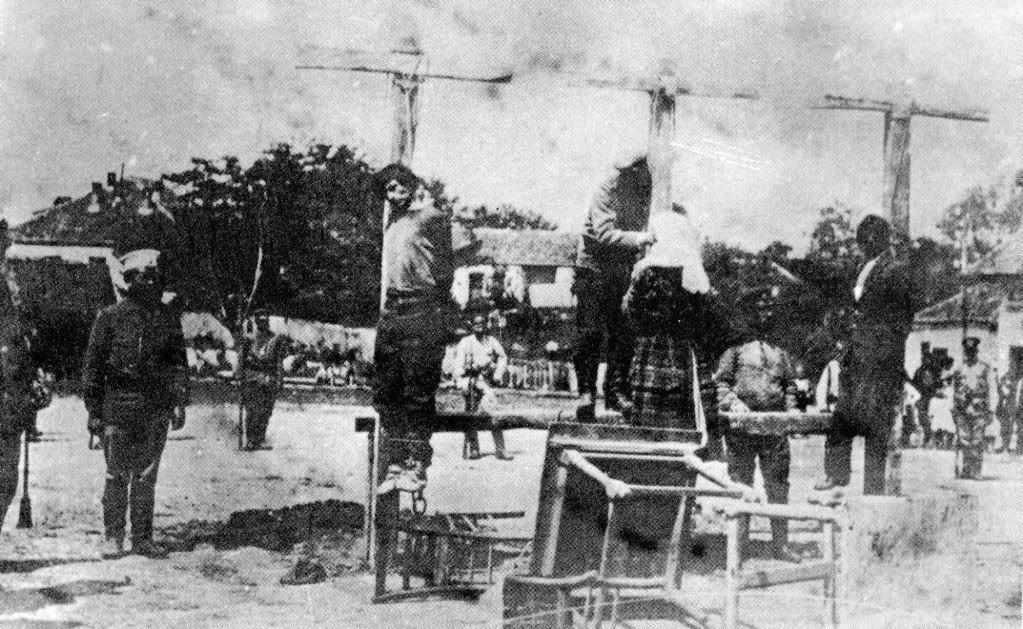

Kruševac, Serbia – 1914: unarmed Serbian peasants hanged by Austro-Hungarian troops without judicial trial and without verdict. Their crime – publicly outspoken verbal insults regarding the Emperor

Ćuprija, Serbia – 1916: Bulgarian troops are hanging peasant woman and a crippled teacher without judicial trial and without official verdict. Their crime – dissemination of enemy propaganda

Bitola, 1916 – Civilian victims (whole family) of Bulgarian poisonous gas attack carried out by unidentified artillery unit

Kuršumlija – 1917: 19 years old Serbian peasant girl whose leg was cut off with Bulgarian’s soldier bayonet after the attempted rape

Discussion questions are:

1.) Are these examples of aggressive human behavior, exclusively committed by different members of certain inherently democratic societies, somehow connected with Nazism or Communism, and if they are how?

2.) Do these sorrowful examples provide sufficient evidence for the assertion that democracy remains the most flawed, confusing and frightening sort of government, which is completely incompatible with personal security of different human beings during wartime hostilities?

After our hopefully fruitful theoretical discussion, we will examine some other historical examples which are directly connected with certain misdeeds with reference to the cases of indiscriminate bombing of an enemy’s cities before the WW2.

Hopefully, we shall expel our tiny ethical rabbit from its historical burrow. And with your kind permittance I shall represent the Crown.

In the meantime, as always - all the best!