Huge THANK YOU to Mr. Slim Fan for editing my lousy English translation and giving it grammatic and stylistic sense!

This part has been edited by him. He also edited the previous parts which I now will replace (Done!). So you may as well re-read them again.

- 10 -

The celebration of 1st of May ( http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Workers’_Day ) approached. Major Pehota, who as I mentioned was our “zampolit” ( remark: Commander’s deputy for political work – not to be confused with “Commissar” ), was very busy with the preparations. Knowing that I was a student before the war he offered me the opportunity to join his orderly, Buriak, in making a newspaper poster dedicated to the celebration. Buriak was a boy aged about 14 or 15 and was regarded as our “regiment’s son” [remark: “regiment’s sons” were usually orphans picked up by the regiments on their campaigns. Hence the name “regiment’s son” indicating that a child had been adopted by the regiment]. He wore a uniform and was always “sticking his nose in everywhere”, hanging around the newcomers, reading aloud from the newspapers distributed by [i]Sovinformbureau /i. Together we began the work. I was responsible for the design and layout and Buriak for the content – for which he went around the platoons collecting material. I remember how our zampolit Pehota criticised me because a German tank with swastika drawn by me did not look as though it had been disabled. I had to redraw it more vividly. This time he was pleased. The tank was depicted with a fractured gun barrel, a huge gaping hole in the side and a broken track. Our tanks were rushing forward belching fire and smoke.Around 26th April we again had a “bath day” and after that received new sets of cotton uniforms. We got English boots, puttees and old patched grey

greatcoats. It was apparent that the greatcoats had already seen combat, but had been cleaned before being given to us. We knew that the fallen were

buried in common graves without their greatcoats, which had to continue to serve, this time to other people.Once in uniform we immediately became indistinguishable from one another. Our field caps fitted our shaved heads very well; though the red star badges were missing and there was no possibility of replacing them. But we found a remedy: we made stars ourselves out of tin and attached them to the field caps with thread. On the eve of 1st of May the remaining troops arrived from the Don, Rostov and Donetsk provinces. Some of them said that they had been working on windmills for the army, others worked on some army farms, but the main occupation was loading and unloading the trains.

Even though we all wore uniforms and looked alike, the odessits [remark: recruits from Odessa] still stood somewhat forward showing a special Odessa disposition. Major Pehota made me responsible for politinformations - reading aloud every day the official front reports and make regiments “battle leaflet” [remark: a kind of in-house newspaper].

After the celebration day the combat engineering forces repaired the railway tracks, and trains started coming in to Razdelnoe station. Our battalion was also involved in the loading and unloading work. In their haste to retreat, the Germans had abandoned a large number of loaded railway cars on the 70km stretch between Odessa and Razdelnoe. There were even two German armoured trains and a train loaded with tanks at Razdelnoe station.

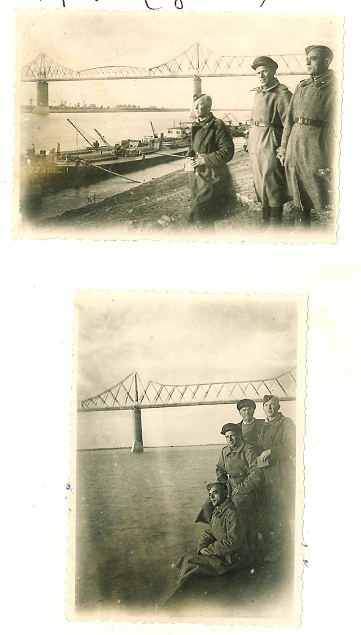

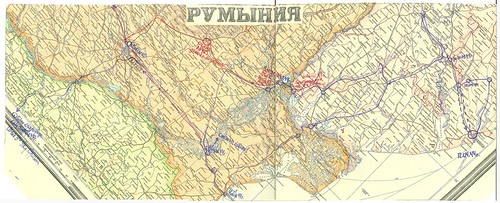

Apart from our battalion, General Pliev’s cavalry division was also stationed in Razdelnoe. But now, in the process of being transferred to another stretch of the front, they were leaving us. The frontline stabilised along the Dnestr river and Tiraspol was now adjacent to it. That frontline was not far from us, maybe 12 - 15 km, and we could clearly hear the artillery at work.

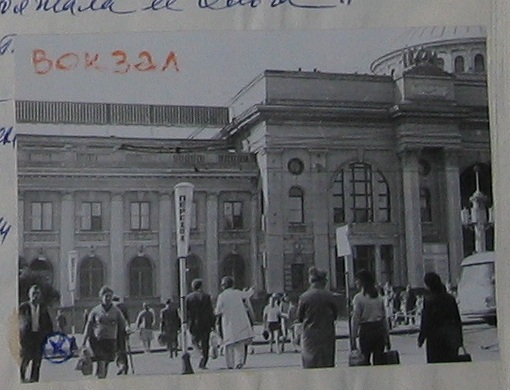

In May the battalion’s headquarters were relocated to the German village of Baden ( remark: there were more than a million German colonists living in the USSR ) on the coast of Dnestr estuary. The inhabitants had left. Probably they fled west together with the German army. There was a station by the name of Kuchurgan about 2km from Baden. Our First Platoon from Second Company was stationed there in an open field guarding a store of chemicals in an abandoned German ammunition dump. It was encircled by barbed wire. Our battalion staff officers were short of writing paper for their work and the only place to get more was Odessa. So they began looking for two people from Odessa willing to procure more paper. Naturally, this operation was not budgeted for and the procurement required promtness and a certain native wit. Since I myself needed paper for my “battle leaflet” I agreed to go on the business trip. I was delighted with the opportunity to return to Odessa, to meet Olga and her parents, and to catch up on their news. I had agreed to go, but I really had no idea where I would find writing paper and how it would be paid for.

[ to be continued ]