I think it very fascinating to learn of another’s experience and memories of the war…as was said before, it is insight inside the Americans haven’t had…

yes…ofcourse it would be very nice to learn other people’s experience…

- 30 -

I went to look around the railway station. It was small single-story building. The stationmaster’s office was abandoned. Telegraph equipment and the station’s seal stamp were on a table. Just for fun I used the seal to stamp paper forms spread around on the table. From the railway tracks I went down to the bank of the Danube. Most of the river ice had gone but some ice floes were still floating down the river. But what was that in the water?

Rolling from side to side, a woman’s corpse was floating in the roiling river. It almost seemed like she was swimming, and that at any moment she would raise her head out of the water… I looked carefully around at the water’s surface and noticed several more corpses. Much later, after the war, I learned that the Hungarian Fascist dictator, Szalasi, sensing that the end was near, ordered the elimination of prisoners at a concentration camp and in the Jewish ghetto. The victims were shot and dumped into an ice-hole on the Danube somewhere further upriver from Budapest. That is how I accidentally became a witness to that crime against innocent people, or rather the result of it.

Our unit’s stocks grew in size. The used shells were piling up and up. We sorted them into separate piles according to their calibre. The biggest of them was from the 152mm howitzer. It was the most expensive one because it was made of brass and weighted 7kg. The others were 100mm, 75mm, and 45mm sizes. To highlight the importance of our work we were told that a single 152mm brass shell was worth as much as a pair of high boots. Well, though we had plenty of brass shells, our boot supply was scarce. Everyone was after a pair of kersey boots – the object of soldier’s wildest dreams.

By that time the Germans had learned to produce shells made of more readily available materials, and were making regular use of steel shells. Those were collected and piled separately. The empty ammunition boxes were also gathered and sent back to the USSR filled with the used shells.Once, we were woken by huge explosions at the nearby station of Budafok. The series of explosions continued all night, and even into the morning. Apparently, a whole train, loaded with ammunition, was attacked. The rumour had it that it was the result of saboteur’s action. One had to be on alert. The enemy could take advantage of any lapse.

Apart from loading /unloading the trains, we also patrolled the adjacent territories and manned the roadblock, checking the civilians’ papers and IDs. Travelling was allowed only with the appropriate stamp issued by the military commandant. One day, at the roadblock, I unexpectedly met a guy who I knew from the ‘Chervony Hutor’ farm near Odessa. He was driving a “Studebaker” and stopped to greet me. We were glad to see each other. At the end he gave me 2 bottles of Tokaj wine stored under his seat. Neither of us could drink – he was driving and I was on duty. But later the same day these bottles were much appreciated. Such reunions were a part of our life in war. They always brought joy.

Sometimes, in the evening, we got some free time from work and patrolling duty. These hours were mostly taken up with dancing on the outskirts of Nagytétény. The local Hungarian women would also come to the place, attracted by the music. The young girls didn’t refuse our invitation for a dance. My usual dancing partner was not there and so I normally danced with a young Hungarian girl Erzy (Or Eugenia in Russian). She was cute and shy, but I gradually gained her confidence

and took her under my wing. She lived just next to our camp and worked in the nearby clothing factory. Her parents were in territory still to be liberated. An old couple, her relatives, helped her out. Eventually I fully won her trust. She often invited me to her place in the evening for tea. I brought sugar and provisions with me. Sometimes her girlfriends were there too. We would dance to gramophone music. As a token of our brief international friendship, she gave me her photograph, which she had at that time.(Erzy’s photograph goes here. See photo 1 in attachments.)

In the end of February – beginning of March, Buda, the right bank side of Budapest, was finally taken by our forces. Our company leader, S.Lt. Sokolov, and other officers, took me and some other soldiers (Silonov, Pushkarev and Paramzin) for a visit to Buda. We mounted a couple of two-horse carriages and approached a big city, which appeared to be badly destroyed. The signs of recent fighting were everywhere: cracked asphalt, craters from explosions, broken glass from windows, rubble, electrical wires and knocked over poles, destroyed German armoured vehicles and trucks. Some houses were still on fire. In short – a scene of carnage.

We stopped and left the carriages at the Gellert Hill and walked up to the castle to see the city’s panorama from above. The castle was the site of the Germans’ last stand in Buda’s defence. Here and there some corpses still lay, but the POWs had already been taken from the castle.

The view to the city from the height was magnificent. The Hungarian Parliament, with a huge cupola in the middle, stood almost in front on the other side of the Danube. The remnants of 4 beautiful bridges fell into sight. They had been blown up back in the winter. Soviet engineers were working on one of them, hastily trying to restore traffic flow across the river.

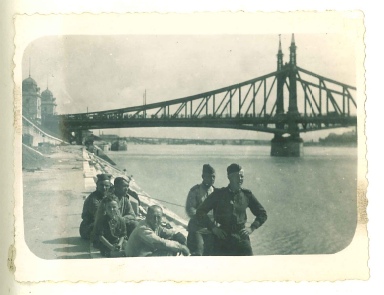

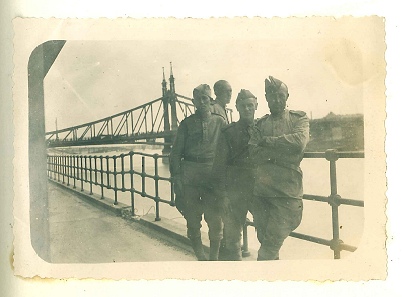

(3 photographs in Budapest go here. See photoes 2,3,4 in the attachemnet.)

To get to the Pest side of the city, we had to go around as the bridges were still inoperable. After a lot of circling in the centre of Pest, we again reached the Danube’s bank, but this time next to the Parliament. We could not enter the Parliament as all the doors were tightly closed, but I managed to take a part of the Hungarian Parliament with me as a souvenir. It was a keyhole lid from one of the entrance doors (right wing). This relic I still keep in my memorabilia collection, which I gave to my grandson, Igor, on his birthday.

Pest was swarming with civilians working on cleaning the streets, removing the rubble and the barricades, filling in the trenches. But the shops were still closed, the food supplies were scarce. People were dressed in working clothes and were running around moving stuff, using for that purpose baby carriages, wheelbarrows and backpacks. Everyone was preoccupied by his own business, and was in a hurry. The walls of houses were covered with new Hungarian newspapers – “Neigabadshag” (remark: spelling???) – the Communist one and by other ones too. Hungarian and Soviet flags were waving around. Posters and slogans in Hungarian. Two graves in a small square in front of a Cathedral – the graves of two Soviet bearers of truce flag shot by Fascists - the graves covered with flowers.

Description of the following 4 photographs:

[ol]

[li]Erzy (on the left)

[/li]> [li]In Budapest, 1945. Zampolit, Captain Nazarenko and company leader S.Lt. Ivanov. “Csepel” river port.

[/li]> [li]On the bank of Danube next to the parliament building. Klimov is on the front. Sitting – moskovit Pushkarev, then – Litovchenko and Silonov.

[/li]> [li]Seregin, Silonov, Litovchenko and Pushkarev. The bridge was blown up by the Germans after their retreat from Pest to Buda in January 1945.

[/li]> [/ol]

[ to be continued ]

Thanks for posting Egorka, and the hard work. It’s nice to see your grandfather was able to keep so many photographs, my father only has a few saved from his time in service back then.

- 31 -

Time passed. We were still at Nagytétény station. One day my platoon leader, Sgt. Zhitovoz, called me over and told me that I was to escort the next train, and to make the necessary preparations. Though it was an interesting task and a sign of his trust in me, I did not really want to leave our camp. We had just been informed that the rest of our unit, including Senior Sergeant Ms. Mohacheva, was to be relocated here from Timisoara. I really wanted to meet her again. But 26 empty train cars came in and were loaded with used shells in 2 days. I prepared a little heated goods van for my self, set up a little cast-iron stove, loaded half of the van with firewood (broken wooden ammunition boxes), and made a plank bed for myself. I also received 5 days dry rations and a food certificate. I was also issued with travel documentation: a piece of paper stating the purpose of my trip and my destination. The train was bound for the station at Reni, i.e. right to the border of the USSR. There the load was to be transferred to train cars of the standard Soviet railway gauge. Everything was ready, but we could not leave because of some rail track problems at the pontoon rail bridge across Danube. The rail bridge had been destroyed and our engineers were working on it night and day, as it was very important for further operations by the forces of the 2nd and 3rd Ukrainian fronts.

But thanks to this delay, I managed to see Maria and all the others. When we finally met, everyone had stories to share. The reunion with Maria was warm and it was obvious that it had been keenly anticipated by us both. I said that I was currently living in a railway van, waiting to leave at any moment. Maria replied that she would visit me in the evening when she was off-duty.

After dinner we, as usual, had some accordion music at our improvised “dance floor”. But I did not join the rest of the guys – I was sitting smoking in my railway van with my legs dangling out. Then I noticed two figures walking along the train. It was Maria with her friend Galina Reviakina. Soon Senior Sergeant Reviakina left to dance with others. Maria came up into my railway van and I closed the door, fed the stove some wood, and took out a bottle of Hungarian Tokaj wine. Maria stayed with me the whole night, taking advantage of the fact that female personnel were lodged in private apartments and were free from attending evening roll call.

Two days passed that way. Then I got a message from the station administrator, with whom I had kept in contact, that the steam locomotive would be arriving in 15 minutes and would then leave right away. It was to take the route along the right bank of the Danube as the railway bridge in Budapest was still inoperable. So I left without saying goodbye to Maria. That day I noticed that the cannonade was louder and that there were more airplanes in the sky than usual. The locomotive, covering no more than 30km, stopped in the evening at the little station of Ercsi. The actual settlement with the same name was situated about a kilometre away from the station, which was completely deserted. The only person around was a station operator, a Hungarian railway employee. Despite the fact that it was night, the cannonade only intensified! I even got feeling that it was coming in my direction. The next morning the locomotive was detached from the train, and it left to get fuel and water (that is what the station operator told me). The whole day went by, but the locomotive hadn’t returned. Another night went by – still no sign of the locomotive. The cannonade was sounding ever louder and closer. The station was still deserted. The toilets at the station were soiled completely – I couldn’t even enter them.

I began to think what would happened if German tanks should get through. The only weapon I had was my SVT and a case of cartridges (though I had really plenty of those). It was then that I noticed some ruins not far from the station. Approaching them I realised that they used to be a Hungarian weapons depot. I figured that out from the remains of the rifles and handguns lying around in the ashes. Only a small shed remained intact. There I found a box of Hungarian hand grenades and a box of primers for them. I decided that before taking the box to my railway van I should test them first in a nearby ravine. I inserted a primer and threw a grenade. The explosion duly followed three seconds later. I tested few more of them, trying charges of different size (the Hungarian grenades are made so that it is easy to attach more explosive to them). Then I took the box to my shelter in case of an attack on me. Rumour had it that an attack could be expected even from civilians. Such incidents had happened more than once. Making sure that the locomotive was not to be expected within the next couple of hours, I went to the settlement. My plan was to get some water and, if possible, to buy some food.

[ to be continued ]

I think it is absolutely awesome that detail and memories can be documented like that. What a privilege.

- 32 -

Ercsi - a small town not far from Budapest.I put an empty water canister in my back pack, and with my rifle over my shoulder went to the settlement. Ercsi was small, but it was cosy and neat looking. A small church was in the centre with a school building next to it.

I barely managed to get a bucket of potatoes and a bottle of milk. Bread was nowhere to be found. Anyone I asked would reply “Nich” (No). I also managed to acquire a couple of corncobs. And that was all. After filling the canister with water from a well, I went back to my train. The locomotive was still absent. Meanwhile I noticed that the cannonade from the direction of the Balaton and Velencei lakes had quietened significantly. Soon after that the locomotive arrived, though it was a different one with a different operator.

Finally my train departed. Though at some stations, or simply at a semaphore signal post, it would stop an hour or so. It was very annoying. At the station of Pusztaszabolcs the signs of recent fighting were apparent. The station building was destroyed. The station supervisor was using a rail car as his office. We passed Adony station – the same wreckage. Then the train went to Szekszárd through an open plain. The snow had melted. My car had a break platform and a conductors booth, which was elevated over the car’s roof, giving a good view over the train. It was also useful for keeping an eye on the sky for a possible attack, though our air force dominated the sky. In the evening we arrived at Baja where we had to cross the Danube over a pontoon rail bridge. I had never before had such an experience. It was difficult to conceive that it is possible to lay rails over such a structure. But here the moment had come. My train slowly rolled to the other side, bending the rails and rocking over the waves. In the morning we arrived at the by now familiar Yugoslavian town of Subotica.

In Subotica I took on 3 passengers – Yugoslavian partisans who were to go to Kikinda. Such great fellows! Real friends! One of them was badly injured in recent fighting and the two others were escorting him home. They told numerous stories about their fighting in one of the Tito’s partisan units. They went through a lot of hardship: hunger, cold, hard mountain marches. Their power, the power that got them through the ordeal, was in their burning hatred of the German occupiers.

Another episode from my trip stuck in my memory. The train approached the town of Szeged. It was a wonderful sunny early morning. I climbed onto the roof of my car for a better view of the town. I had passed through this town several times, but never got a real opportunity to actually see it. On the approach to the rail terminal I noticed the wreckage caused by the American mass air bombardment. Big bomb craters were visible everywhere. It seemed the air raid was conducted the previous year when the town was still in German hands. I knew that large formation of American bombers conducted such raids from Italy and from the Ukraine. Suddenly my thoughts were interrupted. I was blown off the conductor’s booth and fell to the roof of my moving car. Apparently I caught a wire drawn across the rail tracks. I was lucky to fall onto the car’s roof. It could have turned out differently, had the conductor’s booth been placed on the other side of the car. In that case I would had fallen under the weels of the train and these lines would never have been written.

During my trip I learned that a large scale offensive of the 2nd and the 3rd Ukrainian front had begun. The offensive was unfolding successfully and soon the fighting moved onto Austrian soil. The liberation of Vienna would not be long.

I stopped in the towns of Timisoara and Bucharest to re-supply my rations according my food certificate. The town of Reni is located on the border with the USSR. Here I delivered the train to the staff representatives, received a stamp and a note in my travel document at the military commandant office, and went looking for an opportunity to roll back to my unit. I got a place in a comfortable German-made passenger car in a trains destined for Bucharest. I shared the compartment with some young lieutenants, who were just graduated from the NKVD school. They were to go to Bucharest. Later, much later, I realised what a difficult task they had to do – to investigate the circumstances of thousands and thousands of Soviet people who were misplaced during war and ended in Europe. At the same time trains were rolling in the opposite direction. Those were loaded with “ostarbejder”, Russians and Ukrainians, forcefully relocated to Germany to work on their total-war program. Now they were going home. Once I witnessed the reunion of a brother and sister. The brother was a private in the Red Army, whereas the sister was travelling in a goods car together with other young women like her, to the Krasnodar region. This reunion was absolutely accidental and impressed everyone around. Two trains on opposite courses had to take a stop on the same stretch of rail. And can you imagine, that their cars stopped just in front of each other. That is how they met after many years of being apart. Tears of both joy and sorrow were in their eyes. Joy that they had both survived. But what might lay ahead?

When I reached Budapest, the train had to cross the Danube over a newly erected temporary rail bridge. Utilising the remains of the old bridge’s piers, and the fallen steel bridge sections, our engineers built a temporary rail bridge. From the distance it looked wobbly, like it was made of matches. A train was rolling over it very slowly and cautiously. The sleepers were squeaking under the load but endured. Looking from the car’s window it felt like our train was hovering over the Danube, as if it was an airplane.

Upon our arrival only one platoon of our regiment remained in Nagytétény with the task of assembling all the other who were, like me, had been sent away. The whole regiment had relocated to the vicinity of the town of Vesprem at Lake Balaton following the advancing front line. The days were tedious. Erzy also left to go to her parents as soon as she learned that her home town had been liberated.

When our group counted about 30 men, we took the train to rejoin the rest of the regiment. We were led by the commander Ivanov.

[ to be continued ]

Just read today an interesting corroboration to this part of my granddad’d story. In the 3rd part my granddad wrote:

“On the third station of the “Big Fountain“ there was a new three-storey school. It appeared to be stuffed with clothes collected from all over Europe after the extermination of French, Belgians, Poles, Jews, Czechs and Slovaks. These Cossack-policemen started to sell or barter the clothes. Some of the clothes had dried blood on them, some had the Star of David – the six-pointed sign that can be seen on the Israel flag today. The clothes were good and fashionable and the Cossacks and Vlasovists sold the stolen goods with little hesitation.”

And here is info from the SPIEGEL interview with Annette Schücking-Homeyer who served as a Red Cross volunteer on the Eastern Front in Ukraine.

http://www.spiegel.de/international/europe/0,1518,674375,00.html

SPIEGEL: Do you know how many people were killed in Zwiahel?

Schücking-Homeyer: A few local Ukrainian girls helped us out in the soldiers’ home; they said 10,000 people had been murdered. In any case, it was a large number, as I realized a few weeks later when the National Socialist People’s Welfare (NSV) opened a huge clothing warehouse in Zwiahel. Since our Ukrainian helpers always had so little to wear, one of the officers asked me if they wanted to have any of the clothes. So I went there with the girls. There was a lot of children’s clothing. Some of our girls didn’t want to take anything; others said “Heil Hitler” when thanking the soldiers. I wrote to my mother about it and immediately informed her nurses in Hamburg that under no circumstances should they take any clothing from the NSV – because it was coming from murdered Jews.

Thanks for the story! (By the way - i’m a jew).

Who would have expected that in a member from Israel?

Shalom!

I am very interested

Some of this seems quite interesting