Last WWII Comanche Code Talker Visits Pentagon, Arlington Cemetery

Visit the DoD “American Indian Heritage Month” web site at www.defenselink.mil/specials/nativeam02/.

By Rudi Williams

American Forces Press Service

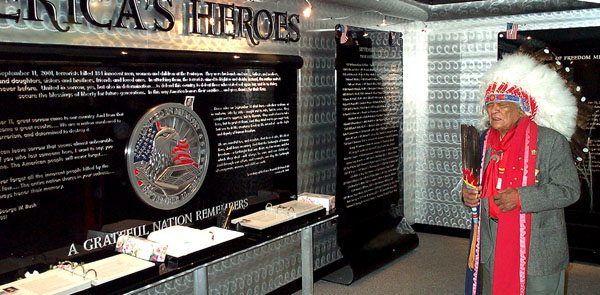

WASHINGTON, Nov. 8, 2002 - After meeting with the defense secretary and other top Pentagon officials on Nov. 5, Charles Chibitty, the last surviving World War II Comanche code talker, donned his feathered Indian chief’s headdress and offered a prayer in the Pentagon Chapel for those killed in the terrorist attack on the building.

The aging code talker then placed a wreath and offered an Indian prayer at the Tomb of the Unknowns at Arlington (Va.) National Cemetery. This marks the third time the 81-year old war veteran was honored at the Pentagon for his service to the nation. His visits in 1992 and 1999 were also in November during National American Indian Heritage Month.

While meeting at the Pentagon with Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, Undersecretary of the Army Les Brownlee and Raymond F. DuBois Jr., deputy undersecretary of defense for installations and environment, Chibitty recounted his wartime experiences when his unit landed on the Normandy shores on “the first or second day after D-Day.” After his unit hit Utah Beach, his first radio message was sent to another codetalker on an incoming boat. Translated into English, it said: “Five miles to the right of the designated area and five miles inland, the fighting is fierce and we need help.”

“We were trying to let them know where we were so they wouldn’t lob no shells on us,” he explained with a chuckle. “I was with the 22nd Infantry Regiment of the 4th Infantry Division. We talked Indian and sent messages when need be. It was quicker to use telephones and radios to send messages because Morse code had to be decoded and the Germans could decode them. We used telephones and radios to talk Indian then wrote it in English and gave it to the commanding officer.”

Chibitty said two Comanches were assigned to each of the 4th Infantry Division’s three regiments. They sent coded messages from the front line to division headquarters, where other Comanches decoded the messages.

He said 20 Comanches signed up to be code talkers, but only 17 went to training at Fort Benning, Ga., and only 14 hit Utah Beach at Normandy. “None of us was killed, but two were wounded pretty badly; one was my cousin,” Chibitty noted.

Brownlee asked him if he was hit and Chibitty said, “Heck, no. I was like a prairie dog. As soon as I heard a whistle, I’d dive in that hole. I was little then. I weighed 126 pounds and it didn’t take long for me to dig my hole. My buddy weighed 240 pounds and some of them were more than six feet tall and they had to dig a long trench.”

Speaking in the Comanche language, Chibitty gave Brownlee another example of a message code talkers sent to other units, then translated it for him: “A turtle is coming down the hedgerow. Get that stovepipe and shoot him.”

“A turtle was a tank and a stovepipe was a bazooka,” he explained. “We couldn’t say tank or bazooka in Comanche, so we had to substitute something else. A turtle has a hard shell, so it was a tank.”

Since there was no Comanche word for machine gun it became “sewing machine,” Chibitty noted, “because of the noise the sewing machine made when my mother was sewing.” Hitler, he said, was “posah-tai-vo,” or “crazy white man.”

There are no other words in his language to describe a bomber aircraft, so they said, "Daddy and I went fishing and we cut that catfish open and he’s full of eggs. Well, that bomber was up there just like this catfish, it’s full of eggs, too, so we called it a pregnant airplane.

“We got so we could send any message, word for word, letter for letter,” Chibitty said. "The Navajos did the same thing in the Pacific during World War II and the Choctaw used their language during World War I. There were other code talkers from other tribes, but if they didn’t train like the Comanche and Navajos, how could they send a message like we did? If they made a slight mistake, instead of saving lives, it could have cost a lot of lives.

In 1989, the French government honored the Comanche code talkers, including Chibitty , by presenting them the “Chevalier of the National Order of Merit.” Chibitty has also received a special proclamation from the governor of Oklahoma. In 2001, Congress passed legislation authorizing the presentation of gold medals to Native Americans who served as code talkers during foreign conflicts.

“I felt I was doing something that the military wanted us to do and we did to the best of our ability, not only to save lives, but to confuse the enemy by talking in the Comanche language,” he said. “We felt we were doing something that could help win the war.”

Brownlee asked him if the Comanche language is written and Chibitty said, “There’s a book, but you’ve got to be awfully damn smart to read it. It’s not like alphabets, you have to learn the phonetics to pronounce the words.” The aging code talker then sang Silent Night in the Comanche language.

Chibitty said when he attended Indian school in the 1920s, teachers became angry with him because he was speaking the Comanche language. “When we got caught talking Indian, we got punished,” he noted. “I told my cousin that they’re trying to make little white boys out of us,” he said.

After joining the Army years later, he told his cousin, “They tried to make us quit talking Indian in school, now they want us to talk Indian.”

The retired glazier visits schools to tell the youngsters about what code talkers did and how they did it. He said officials at Comanche headquarters near Lawton, Okla., are trying to preserve the language by teaching it to children.

“The service you and your buddies provided turned out to be invaluable,” Brownleee told the aging veteran. “You had this way of speaking that nobody could translate. The way you used your language was of such great advantage to your country.”

Before returning home to Tulsa, Okla., Chibitty spent some time with researchers at the U.S. Army Center for Military History for oral history sessions. The Army wants to preserve the history of the Comanche code talkers and Chibitty is the last one to tell the story from first-hand experience.

Ed. Chibitty died in 2005.

JT