D-Day survivor: ‘We were getting mowed down, and they were blastin’ us pretty good’

D-Day survivor: ‘We didn’t ask questions. We took orders’

Jerry DavichJerry DavichContact Reporter

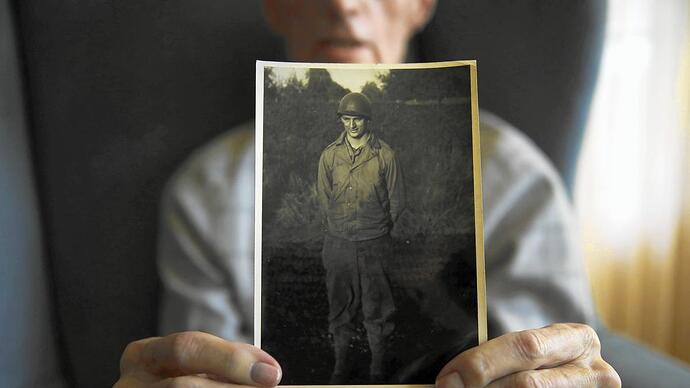

Tom Jensen squeezed his eyes shut to help dredge up memories from June 6, 1944, which is now written in history books as D-Day.

“At that time, we didn’t know it was D-Day,” said Jensen, who was 20 years old that day. “We just knew we had a job to do.”

Jensen was born in Chicago, the youngest of eight kids, attending Pullman Technical High School before enlisting in the U.S. Army on April 1, 1943. He did so without much thought about historic days, heroic acts or the Allied invasion of Normandy, France, which would profoundly alter World War II.

Jensen served Uncle Sam as a sergeant with the 626th Engineer Light Equipment Co., which prided itself on moving, bulldozing or rebuilding anything and everything, from small pillboxes to entire towns. It later received the Meritorious Unit Award and related ribbons for its combat work in Normandy, Northern France, Ardennes, Rhineland and central Europe.

That same unit would later earn the Philippine Liberation Service Ribbon when it was shipped toward Japan after it helped claim victory over Nazi Germany. Jensen’s specialized unit was sent wherever its combat engineers were needed.

“We didn’t ask questions. We took orders,” said Jensen, who’s now 92 and living in Homewood, Ill.

“They didn’t tell us anything we didn’t need to know,” he said. “Heck, some of the guys on our ship thought we were headed to Japan, not Normandy. Just months earlier, we were either in high school or working odd jobs. We weren’t soldiers, at least not yet.”

While traveling aboard a ship from South Hampton, England, for Normandy, headed for what was nicknamed Utah Beach, Jensen and his fellow soldiers heard rumors that Adolph Hitler has devised a “secret weapon” to counter any invasion.

Jensen suspected it was merely wartime propaganda. His fears told him otherwise.

“We honestly figured that at least half of us would be killed by that secret weapon,” Jensen recalled with a chuckle. “That’s what kept running through our head.”

Jensen was one of more than 160,000 Allied troops to land on the 50-mile beach in France. Of those, more than 9,000 were killed, according to the Army.

One soldier on the ship toward Utah Beach kept saying out loud, “Why me? Why me? Why me?”

Jensen countered. “Because the time is now and we’re here to do a job. That’s that.”

This was Jensen’s mindset when he shipped out of New York City for England in February 1944. He clearly remembers staring at the Statue of Liberty in the hazy distance while aboard the HMS Arawa, an armed merchant cruiser.

“I wondered if I would ever see her again,” he recalled. “Or my home and my family.”

While crossing the choppy and dangerous North Atlantic Ocean in a massive naval convoy taking 13 days, two of the ships were sunk by German submarines, he said.

Jensen told the other young, nervous soldiers, “I think we’re in the war, boys.”

In England, his unit was stationed in the small village of Sherston, where he made friends with the town’s baker, Mr. Vining, who he kept in touch with for many years after the war.

“That village was like a fairy-tale Christmas card,” Jensen recalled. “We loved it.”

In the early 1960s, Jensen returned to that village to visit the baker and his family, who later returned the gesture by traveling to Chicago to visit the Jensens’ home.

“During the war, we had no idea if we would ever see each again,” Jensen said. “No one did.”

Jensen’s duty was to waterproof all the military vehicles in his unit.

“To see if they could run underwater if need be,” explained Jensen, who was always mechanically inclined. “As Winston Churchill joked, our trucks were ugly. And they were. But they were made to do a job and, by God, they did that job, even underwater.”

Jensen’s superiors asked for volunteers to first put their boots, M-1 rifle and fate into the water at Utah Beach under enemy gunfire.

“My buddy, D-Day Dan, was the first one in our ship to do it,” Jensen said.

His buddy survived the beach landing, and the war, but not before his body was riddled with bullets from German snipers above that beach.

“We were getting mowed down, and they were blastin’ us pretty good,” Jensen said, again closing his eyes to conjure up those distant images.

He survived that epic beachfront battle and advanced inland with his unit. Together, they built a bridge in Maastricht, The Netherlands, rebuilt war-ravaged roads along the Rhine River in Germany, and dodged or battled retreating German soldiers.

Along the way, Jensen found a German soldier’s helmet, which his unit proudly displayed on their military vehicle while marching across Europe.

“We got 'em now, boys!” they yelled to other units.

Jensen returned home with the helmet, which he still has in his home. It’s only shrapnel from history these days but it still means something to him. Something most of us will never experience.

Jensen routinely downplayed his personal role on D-Day, as well as throughout that war. His son, Chuck Jensen, who lives a few doors down, helped fill in those gaps. Tom Jensen’s niece, Patty Hamilton of Knox, filled in much more about his post-war life.

“My uncle won’t tell you what a great guy he is,” she told me. “How he helps so many people who are less fortunate. How he took care of his wife the last few years as she suffered with dementia. And how he went through 20 radiation treatments last October for skin cancer.”

“Tom Jensen is truly the epitome of a soldier,” she said. “I am so proud of this man.”

Jensen’s wife, Evelyn Rose, died March 18, 2015. She was 88.

“She’s buried at Abraham Lincoln National Cemetery in Elwood,” Jensen said, showing a photo of the cemetery. “I’ll be buried there, too. I could have been killed and buried in France or Europe. But I made it out of there alive.”

Jensen was stationed in the Philippines when he heard news that our country dropped atomic bombs on two Japanese cities he knew little about.

“We thought to ourselves, thank God, this war can finally end,” he said. “And we were right.”

But they weren’t right about another collective conclusion at that time.

“Just after the war ended, when we learned about the doomsday capabilities of the atomic bomb, all of us thought for sure there would never be any more wars,” said Jensen, who was honorably discharged Dec. 23, 1945.

“I guess we were wrong.”