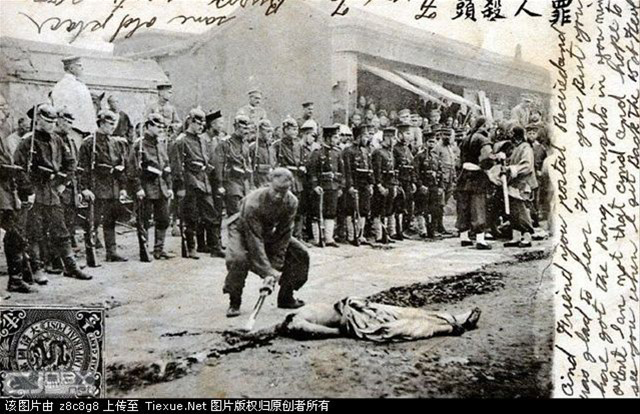

Japanese dishonour in surrendering ensured that few prisoners were available to be taken, while the general practice among Allied soldiers of killing wounded Japanese and not taking prisoners ensured that even fewer Japanese prisoners were actually taken.

The Allied practice was never an official policy, just something that troops on the ground did as a response to endless examples of Japanese brutality and inhumanity towards Allied prisoners on the battlefield and Allied casualties caused by actions by or booby traps on Japanese wounded or dead, and very occasionally from casualties caused by Japanese pretending to surrender.

If the Japanese militarists’ creation of the ‘no surrender’ code and the corrupted Bushido code which generated appalling mistreatment of civilians and service people wherever the Japanese went 1933-1945 had not generated the Allied practice, there would have been hundreds of thousands of Japanese prisoners taken. This would have started in late 1942 – early 1943 in Guadalcanal and Papua with some thousands of prisoners and mounted steadily as the Allies advanced towards Japan, steadily increasing the burden on the Allies of maintaining the POWs.

It has just dawned on me (probably about 70 years after Allied commanders and logisticians recognised it) that this conferred a major advantage on the Allies by avoiding:

- Allied troops and resources being diverted to POW guard and transport duties from the battlefield to staging to permanent camps.

- Burdens on Allied medical services from battlefield level upwards.

- Logistical burdens of housing and feeding prisoners, and transporting necessary supplies by sea or air where local supplies were insufficient.

Contrast this with the guarding, logistical, and medical burdens on the Allies in North Africa and Western and Southern Europe in dealing with large numbers of German prisoners, not to mention huge numbers of Italian prisoners although the latter were rarely wounded in proportion to the total number taken.

At battlefield level, about all the Japanese militarists’ brutal codes achieved was to energise the Allies against them by extremely savage but ultimately pointless mistreatment of Allied battlefield casualties and prisoners. A less brutal but more calculating enemy would have used the casualties to reduce the forces facing them, without energising those forces. For example, on the Kokoda Track and at Milne Bay the Japanese often left terribly tortured and mutilated Australian corpses in their wake. These engagements were often fought on narrow to very narrow jungle fronts at platoon to, in what in some places were major engagements, company level. Finding three mutilated bodies merely energised a company of about 120 men to wreak vengeance on the enemy. Leaving three living casualties needing stretchering would have taken 12 men, or about a third of a platoon or a tenth of a company, out of the battle line to take the casualties back to medical aid.

The unintended consequence of the militarists’ creations was that, once the tide turned against Japan, those creations contributed to Japan’s defeat.

This is another glaring example of the failure, or perhaps inability, of the militarists and their supporters to understand and predict the effect on their enemy of their actions, in the same way that they failed to understand and predict the effect of Pearl Harbor in galavanising American public opinion in favour of total war against Japan.

I’m inclined to the view that (as with some modern Islamic strategic brutalists like bin Laden who favour spectacular but ultimately strategically and tactically inconsequential events which merely ensure a disproportionately destructive response against them and their ilk by a vastly better equipped foe) part of the problem for the Japanese militarists lay in extolling the virtues of their narrow and distorted view of medieval military values which had no place on the modern battlefield against a modern enemy with industrial and technological superiority which, with the ‘spirit’ generated by Pearl Harbor and subsequent Japanese atrocities, would prevail against an industrially and technologically inferior aggressor which saw its racially and culturally pure ‘spirit’ as capable of overcoming all.