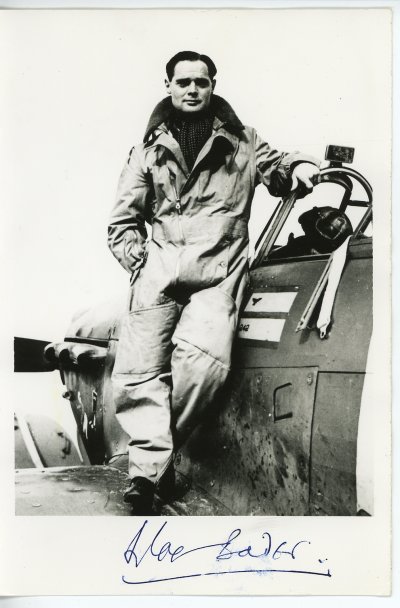

Perhaps more than anybody, Douglas Bader epitomised the British bulldog fighting spirit so needed during the Second World War. Fuelled by the desire to prove he could still fly an aeroplane after having both legs amputated, and also by his burning hatred of Adolf Hitler, his actions as a fighter ‘ace’ greatly exceeded the call of duty.

Born in London in 1910, Douglas Bader was immediately separated from his parents who left for India. He was reunited with them when they returned to Britain in 1913, but a year later Douglas’ father, Frederick, left for France to fight in the Great War and that was the last he ever saw of him (Frederick Bader died in France in 1922). Perhaps the fact that he never had a father figure to turn to, contributed to his unique psyche in later life.

At school it soon became obvious that Douglas had a natural flair for physical sports, particularly rugby. He also had exceedingly strong leadership qualities, which resulted in him being given the responsibility of captaining the rugby team.

Shortly after leaving school, whilst staying with his aunt and uncle, Bader decided that he wanted to join the RAF. His uncle obviously persuaded him to some degree; he had worked in the RAF for some years. Other family members disapproved though, but he was undeterred, and by 1928 he had gained his cadetship.

During his training for the RAF, he became notorious for not following orders, and his commanding officers began to see him as a thorn in their sides, immature and quite unsuitable for the armed forces. Their feelings were confirmed when the results of a mid training progress exam came through – Douglas Bader had finished very near to last. Because his flight skills were superior though, he was given another chance, but not before a dressing down by one of the senior officers, who made it clear he was in a man’s world now, not some school dormitory. Bader responded magnificently, and graduated into the RAF, narrowly missing out on receiving the Sword of Honour, awarded to the best graduate of the year.

He was posted to Kenley, and it is there that disaster struck. Challenged to perform various acrobatic stunts, Bader protested that the Bulldog planes that they had begun using were very different from what he had been flying, much heavier, and as such he wouldn’t be able to perform the stunts safely. Eventually he was goaded into it though. Tragically, he was proved right. The Bulldogs were much too cumbersome for low-level stunt flying, and Bader crashed. Both legs were mangled in the calamity, and he was taken straight to hospital to see a top surgeon. The surgeon immediately amputated one leg, and a few days later was forced to do the same to the other. Nobody thought that Douglas would live, so bad had been his accident, but amazingly he pulled through.

After recovering somewhat, Bader was transferred to an RAF hospital, where he was left to convalesce. It was here that he met Marcel Dessoutter, who had lost one leg in an air accident. Subsequently Dessoutter had developed a business selling metal alloy false legs for amputee victims. Bader immediately volunteered to try some out and was kitted out with two tin legs. Gradually he taught himself to walk on them, enduring horrific pain along the way and not once using the aid of a walking stick – a remarkable feat. The progress continued when Bader had a car modified so that he could drive it. As a consequence he got his opportunity to fly an airplane again, and he jumped at the chance. After so long though, and with no real legs, his performance in the cockpit was at best shaky. In 1933 the RAF officially retired him.

It looked as though the military career of Douglas Bader was over. He acquired another job with the Asiatic Petroleum Company, and met Thelma Edwards who he married. All the time though, at the back of his mind was the desire to get back in the cockpit of an RAF fighter plane.

His chance came at the outbreak of World War Two. The RAF reassessed him and allowed him to fly. He worked his way through the lesser planes until he eventually had control of the renowned Hawker Hurricane. He got his first kill in Dunkirk in 1940, and shot down 22 enemies in total becoming renowned as an ‘ace’. Following the Battle of Britain he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order and the Distinguished Flying Cross for gallantry and leadership of the highest order.

Bader’s amazing aura of invincibility was broken in 1941 when the plane he was flying collided with a German Messerschmit, and the Nazis captured him. After trying to escape several times he was transferred to Colditz, where he stayed until 1945, the end of the war.

Upon his return to England he was chosen to lead the three hundred plane victory flypast, over London, so highly was he regarded. He left the RAF a year later – the tedium of military service in peaceful times was no longer a desired option for him. In 1976 he was knighted, for the services he has given to amputees. Six years later he died of a heart attack aged seventy-two. Without the courage shown by people like Douglas Bader, the war may well have been lost.