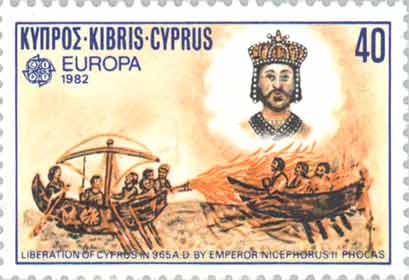

Greek Fire was a kind of flamethrower weapon. The fleet of King Ihor (or Igor) of Kiev encountered Greek Fire during his 941 A.D. invasion of Byzantium according to the RUS (not Russian) chronicler in the Primary Chronicle. The Chronicler wrote: “The Greeks possess something like the lightning in the heavens and they released it and burned us. For this reason we did not conquer them.” However, according to tradition, King Oleh in 907 A.D. did mount his shield on the Gates of mighty Constantinople.

http://www.infoukes.com/history/inventions/

GREEK FIRE

“Greek fire” was a weapon employed by the Byzantines, and its nature remains as mysterious today as it was in the 7th century when it was first unleashed. It was instrumental in saving Constantinople from invasion by Muslim fleets in 678 and again in 718. Such a veil of secrecy surrounded the weapon that, in time, the Byzantines themselves forgot how to produce it.

Incendiary weapons were nothing new in warfare in the Mediterranean world. Naphtha, a petroleum distillate, was known in the 4th century BCE. In combat on both land and sea, petroleum, sulphur, bitumen, and resin had been used since early Christian times. But Greek fire was more insidious. It was projected upon enemy forces in the fashion of a flamethrower. Contemporary accounts frequently mention the mixture being discharged from tubes mounted on the prows of Byzantine ships. Like modern napalm, it adhered to whatever it struck, and could not be extinguished with water.

The Byzantine historian Theophanes credits its development to a man called Calinicus, a Syrian refugee from the Arab conquest. We still do not know its precise chemical composition, nor do we know exactly how it was ignited. It may have been a mixture of distilled petroleum (similar to modern gasoline) that was thickened with resins and sulphur. This would have prevented it from being quickly extinguished or washed away by water. The Chinese possessed a similar weapon in the 10th century that was ignited with gunpowder – something unknown to the Byzantines in the 7th century. One hypothesis suggests that the Byzantines stored the mixture in vats and projected it with a type of force pump of the sort attributable to the Hellenistic inventor Ctesibius. An 8th century account speaks of iron shields that sheltered the men who operated the bronze “flamethrowers,” and the author also describes the thunderous noise that the weapon emitted as it discharged. This noise has led some scholars to speculate that the Byzantines may have indeed known how to make gunpowder at that time, but this is by no means certain. The exact nature of the weapon was a state secret known only to a small circle of Byzantine elites. The infrequent record of its use after the defence of Constantinople in 718, and the poor performance of the Byzantine navy in subsequent years, indicates that the secret of Greek fire had been lost to its users. But even secret weapons do not usually remain completely secret, and the Arabs themselves managed to develop a version of Greek fire that was used for some time to come.

Ambiguity even surrounds the weapon’s name. The term “Greek fire” was coined by Western European crusaders in the 13th century - quite some time after the method of producing the weapon in its original form was lost. One of its original names was actually “Roman fire,” since the Arabs, Russians, and Bulgars against whom it was used saw the Byzantines as Roman rather than Greek. The Byzantines themselves termed the weapon “marine fire,” “liquid fire,” “prepared fire,” or “artificial fire.” Despite its shrouded nature and its limited use, Greek fire is a good example of how a single weapon can alter the balance of power and, if even for a short period of time, alter the course of history.

http://www.ucalgary.ca/applied_history/tut…/greekfire.html

They remade it on the history channel and tested it out to see if it would work. It infact did and worked rather nicely I think. Pretty amazing given the time it was invented. 8)