Generals foiled Aug. 15 palace coup

Pair’s actions credited with ensuring Hirohito surrender decree

BY MUTSUO FUKUSHIMA

KYODO NEWS

AUG 12, 2005

ARTICLE HISTORY

PRINT SHARE

Hours before Emperor Hirohito decreed Japan’s World War II surrender 60 years ago, two Imperial army generals foiled a coup attempt by a dozen officers to block the historic broadcast.

On Aug. 15, 1945, nearly 1,000 soldiers occupied the Imperial Palace grounds for six hours from 2 a.m., aiming to seize two 25-cm records of the reading of the surrender decree and blocking its noon broadcast that day.

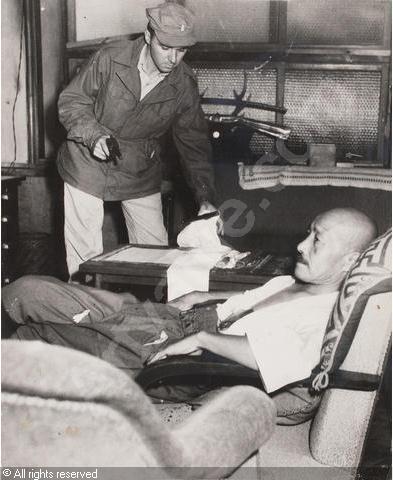

The actions of Lt. Gen. Takeshi Mori, commander of the First Imperial Guards Division, and Gen. Shizuichi Tanaka, commander of the Eastern Defense Command, enabled the monarch, known posthumously as Emperor Showa, to announce over the radio to the Japanese people and armed forces the nation’s unconditional surrender.

The broadcast paved the way for the Allied Powers to occupy Japan without serious turmoil.

Emperor Hirohito made the recording at around 11:30 p.m. on Aug. 14, and Chamberlain Yoshihiro Tokugawa put the two records in a small safe in the first-floor office of the monarch’s retinue, hidden from sight with piles of papers.

At around 1:40 a.m. on Aug. 15, Mori, 52, was shot by Maj. Kenji Hatanaka and then hacked to death by Capt. Shigetaro Uehara at his headquarters after rejecting their demand to order his 4,000-man division to revolt against the government and seize the palace.

“Mori rejected the officers’ demands to order his Guards Division to rise up in revolt, because he had recognized the importance of establishing peace with the Allied Powers to prevent the Japanese people from being destroyed by a continued war,” historian Kazutoshi Hando said in a recent interview.

“Had the broadcast of the surrender rescript been blocked, the Japanese military would have kept up its fighting spirit, and the armed forces would have carried on on many battlefields,” he said.

On Aug. 14, the government of then Prime Minister Kantaro Suzuki decided to accept the Allied demand for unconditional surrender. The decision was made at a meeting of the six-member Supreme Council for the Direction of the War, including Suzuki and War Minister Korechika Anami, in the presence of Emperor Hirohito.

At around 2 a.m. the next morning, Maj. Hidemasa Koga, Guards Division staff officer and son-in-law of Gen. Hideki Tojo, the prime minister at the time of the 1941 Pearl Harbor attack, issued a bogus order for the 1,000 soldiers to occupy the palace, seize all gates and cut all telephone lines except one linking the palace to the Guards headquarters.

The order was aimed at isolating the Emperor from the outside, preventing him from asking the government or any forces inclined toward peace, including the Eastern Defense Command, for help, and toppling the Suzuki administration to form a new government led by War Minister Anami.

The Eastern Command, led by Gen. Tanaka, was in charge of defending the capital.

The coup leaders affixed the official seal of murdered Division Commander Mori to copies of the order, tricking the division’s field and company officers into believing it was authentic.

In addition, a 60-man company of the Guards Division’s First Regiment occupied NHK, then based in Tokyo’s Uchisaiwaicho, and prohibited all broadcasts. NHK was then 1.5 km away from the Imperial Household Ministry, the predecessor of the Imperial Household Agency.

“I heard three bangs when I was on sentry duty in an air-raid shelter outside the room of Division Commander Mori,” said Ikuo Okazawa, who was a 24-year-old lance corporal in the division’s Second Regiment at the time of the assassination.

Okazawa, now 84, claimed he initially thought the three bangs might have come from a motorcycle being started nearby.

Shortly after the shots, 2nd Lt. Tamiharu Sasaki came to the shelter and ordered Okazawa and three other soldiers to make “a pair of wooden boxes large enough for a person,” as well as lids.

“We went to a nearby First Regiment barracks, and tore up the floorboards to make the boxes,” Okazawa, a former legislator of the town assembly of Kamigori, Hyogo Prefecture, said in a recent interview.

An hour later, Okazawa and the others took the rough-planed coffins to the commander’s room.

Then, “2nd Lt. Sasaki, loosening his sword, told us he would hack us to death if we said anything to anybody about what we were going to see upon entering the room,” he said.

“When I entered the room, I found the bodies of Mori and his brother-in-law, Lt. Col. (Michinori) Shiraishi,” he said. It was only at that moment that he realized the boxes he had made were coffins, he reckoned.

Shiraishi, staff officer of the Hiroshima-based Second General Army, had come to Tokyo the previous day and called on Mori, his wife’s older brother, before he was to fly back to Hiroshima.

“My estimate is that the number of soldiers who entered the palace premises was more than 1,000. . . . Those who invaded the Imperial Household Ministry building to seize the recordings of the rescript numbered between 40 and 50,” Masahisa Enai, a former corporal in the Imperial Guards Division’s Second Regiment and a coup participant, said in a telephone interview.

Enai, 88, became an Asahi Shimbun journalist after the war.

At the Aug. 14 supreme council meeting, Hirohito asked the councilors to prepare the capitulation decree.

“If we continue the war, Japan will be totally annihilated. If even a small number of Japanese people’s seed is allowed to remain . . . there is a glimmer of hope of an eventual Japanese recovery. . . . I am willing to go before the microphone,” he said.

In the subsequently recorded announcement, he said: “I have ordered the government to communicate to the governments of the United States, Great Britain, China and the Soviet Union that our empire accepts the provisions of their joint declaration” issued from Potsdam near Berlin on July 26.

However, despite a series of military defeats in the Pacific, including in the Philippines and Okinawa, the Aug. 6 atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Aug. 9 bombing of Nagasaki, and even Japan’s dispatch of a cablegram on Aug. 10 accepting the Potsdam declaration, there were still plenty of military fanatics who refused to surrender.

Masataka Ida, a coup leader, said in a 380-page memoir that he tried to persuade Mori to order his Guards Division to occupy the palace at a meeting that began at around 12:40 a.m. on Aug. 15.

“Your excellency, if we obey the Emperor’s order, the emperor system could be abolished. . . . A plan has been devised to kill you, though it depends on your response,” Ida told Mori.

The lieutenant colonel quoted Mori as responding: “I am prepared for the worst. I am risking my life to defend the palace.”

Just after Ida left Mori’s room, Maj. Hatanaka and Capt. Uehara entered and learned Mori had rejected their demand that he order the coup. Then they killed him.

Capt. Nobuo Kitabatake, commander of one of the three Guards Division battalions that took over the palace, wrote in his memoir: “If the Imperial Guards Division became the first to rise in revolt, it would embolden the entire military to rise, thus leading Japan to continue the war.”

After the forged order to gain control of the palace was issued at around 2 a.m., Koga and Hatanaka entered the palace, tricking Col. Toyojiro Haga, commander of the 1,000 Imperial Guards on the grounds, into believing the war minister would soon call on the Emperor to persuade him to scrap his decision to surrender.

The soldiers started searching for the surrender records. Capt. Kiichiro Aiura, a leader of a machinegun company with the Imperial Guards Second Regiment, was one of the officers ordered to join the search.

“I was ordered by Maj. Koga to go to the Imperial Household Ministry building and search for the records of the (surrender decree) along with Capt. Shinichi Kitamura, who had already been looking,” he said.

The rebels searched for the recording for 90 minutes, but to no avail.

The plotters suffered a setback when Col. Kazuo Mizutani, chief of staff of the Guards Division, escaped to the Eastern Defense Command and alerted Gen. Tanaka.

At 4 a.m., Tanaka arrived at the barracks of the Imperial Guards Division and persuaded Col. Taro Watanabe, commander of its First Regiment, who was on the brink of sending 1,000 reinforcements to the palace, to disperse his soldiers.

Tanaka then summoned Haga, informed him that Mori had been murdered and that the occupation order was a sham, and persuaded him to order his troops to stand down.

After a furious Haga confronted Koga and Hatanaka, they left the palace and killed themselves. Haga had all of the troops pulled out of the palace at around 8 a.m.

At noon, the surrender recording was broadcast, and the nation heard the Emperor’s voice announcing Japan’s capitulation.

Brig. Gen. Bonner Fellers, an adviser to Gen. Douglas MacArthur, wrote in 1947 of the broadcast, “This historically unprecedented surrender unquestionably shortened the war by many months and prevented an estimated 450,000 American battle casualties.”