At the Conference of the Allies, which took place in Chantilly (France) in February 1918, the Italian Prime Minister, Vittorio E. Orlando, officially requested a Contingent of American troops to be put at the disposal of the Italian Army Headquarters. This had been done in the past with the other members of the Alliance. The American President, Wilson, had to send the requested Contingent, even though his Generals and Commanders disagreed. Beyond the moral reasons, the image, and the duties of the Alliance, there was a great deal of political pressure on the Congress from the large Italian-American community. This facilitated the decision to send an Infantry Regiment to the Italian front, which had a full strength regular combat unit created through the organized aggregation and integration of several minor independent units like a battalion of machine–guns, some batteries of artillery and mortars with logistical autonomy, and complete medical units. The 332nd Infantry Regiment was chosen since it was ready to be sent to Europe. The Generals opposed the decision of providing Italy with American troops that were already fighting on the French front, and requested to send troops that were available in the U.S.A. Actually, the German offensive in France took place in March 1918, therefore it would have been impossible for the Allies to move any of their troops to the disposition of the Italian Army.

But before they reached Italy, because the defeat at Caporetto, in December of 1917arrived in Italy other Americans. They were not combat troops, as in France, but young volunteers of “American Red Cross” who had signed a six-month engagement as drivers of ambulances. In most university students, they were anxious to assist “in the front row” to what the U.S. press, with a cynicism justified only by distance, extolled as “the greatest show on earth.”

It was a small contingent. In all, about 200 men, with responsibility of welfare and propaganda. In practice they had been sent to Italy to give courage to those who fought on the front lines, to cheer the moral after the disastrous retreat, to encourage the resistance because behind there was the great America who was coming (?).

Among them, two future very famous writers: Ernest Hemingway and John Dos Passos.

The novel of Hemingway “A firewell to the arms” was largely inspired by the author exprience on the Italian front.

The Americans were grouped into five sections of the ARC (American Red Cross) with bases in Schio. Bassano del Grappa, Fanzolo, Roncade and Casale sul Sile. Each Section had twenty ambulances “Ford” and “Fiat” available and thirty drivers, used to transport the woundeds from field hospitals to rear. The sections also dealed with management of “rest stops” set up behind the front lines that supplied combatants. In Milan, Via Cesare Cantu No 4, the ARC had arranged for their staff a small but efficient military hospital. When the front was quiet, these American boys in khaki uniform dare to set foot in the trenches where they distributed handshakes, chocolate, cigarettes, coffee and backslapping. For this reason, not knowing how to define them, many people called them “those of chocolate”.

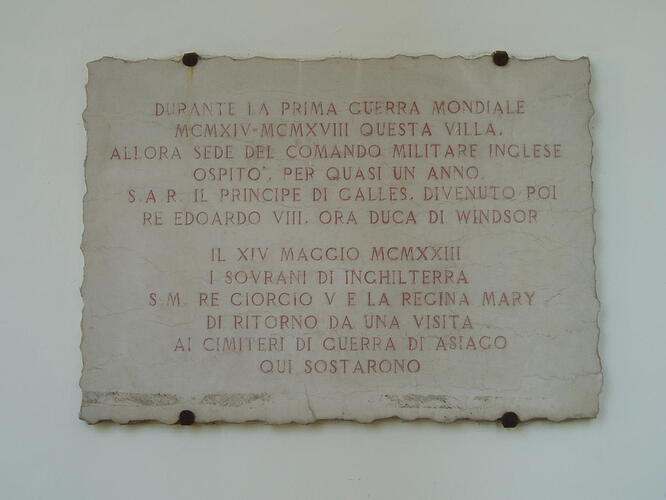

Owing to reasons of supply priorities, the 332nd Regiment could leave the U.S.A. only in May 1918. Together with the entire 83rd Division, they reached Great Britain in June. While they were getting ready to be transferred to France and then to Italy, news of an Austrian -Hungarian offensive in June1918 on the Piave river postponed their departure from Great Britain. A Contingent of about 2000 Officials and soldiers embarked on the Italian ship “Giuseppe Verdi”, and reached Genoa on the 28th June 1918. By train they arrived in Padua where they met with the Command of the U.S. Military Mission. The Headquarters of the U.S. troops in Italy was created in Padua, while the Field-Military-Hospital A.E.F.331 was installed in Verona and the Base Hospital A.E.F. 102 was installed in Vicenza. On the 25th July 1918, the 332nd Regiment, that was in France at the time, was sent to Italy. The Regiment arrived in Milan on the 28th July 1918 and was welcomed with joy by the residents and authorities. The troops at their arrival were welcomed in Villafranca (Verona), too. The 3rd Battalion, the Battalion of Machine gunners and the Companies of Supplies stayed in Villafranca. In Custoza, near the Field-Hospital 331, the 2nd Battalion was quartered. The 1st Battalion and the Regimental Command was quartered in Sommacampagna (Verona) along with the Battalions of Artillery and Mortars. All other minor units were divided among the various Battalions.

The troops were quartered in old Italian Military infrastructures that were put at their disposal, infrastructures that had been used in the past by the Italian Army, but all were lacking in efficiency and safety. Some efforts were made immediately in order to improve the buildings and get them to good levels of cleanliness and safety.

The training for trench warfare started immediately in some areas that had been prepared for this purpose, both for the Infantry and the Artillery, in Valeggio near the Mincio river (Verona). The training took place in August 1918, for all the U.S. units. During the training some accidents occurred and some soldiers were injured. The training had been prepared by the “Arditi” units, a special Italian Army group of assaulters. By the end of August some units of the 332nd Regiment were ready to go to the front. The first to go were the men of the 2nd Battalion, who joined the 37th Italian Infantry Division on the Piave river, in the Candelù sector. The 1st Battalion was kept as reserve, behind the front lines, between Varago and Maserada ( Treviso ), while the 3rd Battalion was finishing the training. By the end of October the whole U.S. Contingent was ready to be sent to the front lines.

During the first weeks of October the units took turns in the trenches on the Piave river between Candelù and Grave di Papadopoli sectors, in an area that was regarded as tranquil, and there was little loss of life. There were, though, some sudden attacks by the Austrian-Hungarian Artillery, which was starting to give in.

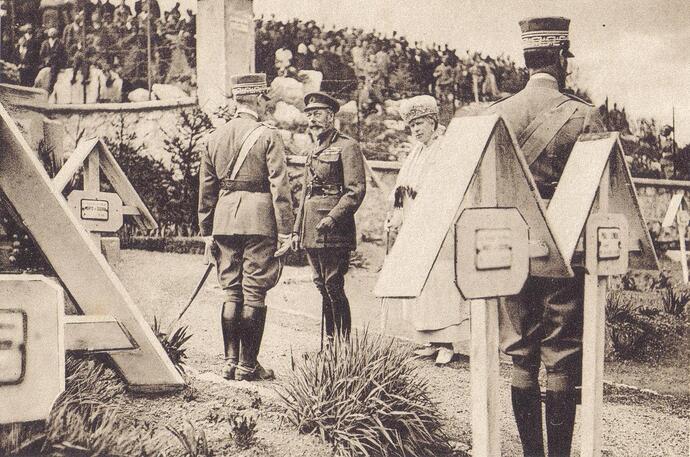

When the offensive of “Vittorio Veneto” started on the 24th October 1918, the 37th Italian Infantry Division was in reserve behind the front lines with the U.S. Contingent. On the 29th of October they were ordered to advance and cross the Piave river, to chase the enemies, who were withdrawing. On the 3rd of November the vanguard of the 37th Italian Infantry Division, which included the U.S. 332nd Regiment, contacted some Austrian - Hungarian units that were trying to resist on the Tagliamento river. At the bridge, Ponte della Delizia, the enemy placed their machine–guns to try to arrest the forwarding Allies. On the 4th of November, in the morning, the Infantrymen of 332nd Regiment attacked and conquered the areas that were occupied by Austrian-Hungarian soldiers and forced them to surrender. Then they ran after those who had managed to escape on the road to Codroipo and Udine. There was very little loss of life. On the same day, at 3 p.m., the Armistice stipulated by Italy and the Austrian-Hungarian Empire came into force and the fighting stopped. The agreements were that Italian Army had to reach and to occupy several areas of Austrian – Hungarian territory.

It was decided that the U.S. Contingent had to become an Occupation Force of the Allies in the territories that had been under the Austrian-Hungarian Empire.

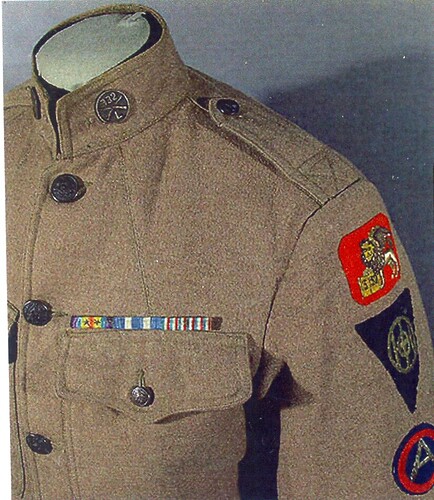

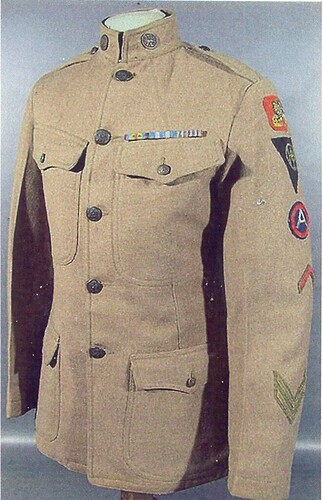

When the members of the 332nd Regiment got back to the U.S.A, they showed off an ornament in red cloth with the lion of Saint Mark in the centre, sewn on the sleeve. The lion keeps a book opened with its claws and 332nd, the number of the Regiment. The ornaments were hand-made most likely in the area around Treviso, but they were unauthorized and out of order unit crests. In the years that followed, these ornaments were officially recognised and authorised by the U.S. Army.

Furthermore, since September 28, 1917 U.S. pilots were training with the Italian aeronautical corp.

Among them Fiorello La Guardia, future beloved mayor of NYC.

The best pilots were then embarked the following year with the Italian bomber groups VI and XIV.

One of them was the leutnant pilot Coleman De Witt from Tenafly, NJ, one of the few foreigners to receive the highest honor of the Italian armed forces, the gold medal.

The aircraft Caproni Ca44 serial number 11669 took off from Tombetta airfield for a bombing action on the front of Vittorio Veneto in the final days of the offensive, while the troops were involved in the passage of the Piave river. On board, a mixed Italo-American crew.

At the controls De Witt and James Bahl, second pilot, with Vincenzo Cutelli and Tarcisio Cantarutti. The aircraft was intercepted and shot down by a patrol of 5 Austrian fighters.

The motivation of the gold medal says: “In the afternoon of October 27, 1918, during an action of bombing, crew chief of a C44 Caproni attacked by five enemy aircraft, instead of evading the fight, he preferred to accept it without hesitation, transfusing strength and energy in his comrades of flight, with his magnificent example of courage and decisiveness. Two of the opponents were downed by the infallible shots of the surrounded aircraft, on board of which the crew continued to struggle amid the flames, until, overwhelmed by the larger number of enemies, it crashed and the entire crew paid with death his audacity”. The co-pilot James Bahl was awarded with the Silver Medal.