Legends of the Burma Campaign – Frank Merrill and the Marauders

INTRODUCTION

The Allies’ aim in the China-Burma-India (CBI) Theater of World War II was to supply and buttress Chinese armies in their struggle against a massive Japanese incursion. The enemy’s seizure of China’s seaports had severed its traditional supply lines. Accordingly, the Allies transported equipment, men and supplies to China through Burma by building roads and pipelines, and India by flying the “Hump” route over the Himalayas. In addition, the Allies aided China by conducting ground and air offensives.

OVERVIEW

Merrill’s Marauders, a Ranger-type regiment, came into existence as a result of the Quebec Conference of August, 1943. The Joint Chiefs of Staff had been so impressed with Orde Wingate, whom Churchill had brought to the conference, that they decided to organize an American commando force to serve with Wingate’s Chindits. Its goal would be the destruction of Japanese communications and supply lines and generally to play havoc with enemy forces while an attempt was made to reopen the Ledo Road.

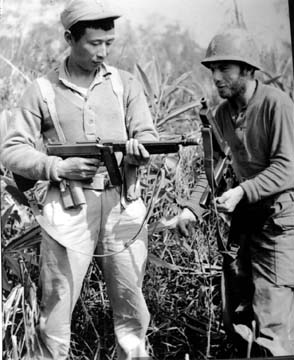

A Presidential call for volunteers for “A Dangerous and Hazardous Mission” was issued, and approximately 2,900 American soldiers responded to the call. Officially designated as the 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional), code name GALAHAD, the unit later became popularly known as Merrill’s Marauders, named after its leader, Brigadier General Frank Merrill. Organized into combat teams, two to each battalion, the volunteers came from a variety of sources. Some came from stateside cadres; some from the jungles of Panama and Trinidad; and the remainder were battle-scarred veterans of Guadalcanal, New Georgia, and New Guinea battles. In India some Signal Corps and Air Corps personnel were added, as well as pack troops with mules.

Preliminary training took place in secrecy in the jungles of India under the tutelage of Wingate’s Chindits.

MERRILL’S MARAUDERS

Plans were drawn up for an offensive to begin with a Chinese-American force attacking North Burma, with the ultimate goal of taking the Myitkyina airfield, which would remove the threat of enemy fighter planes attacking allied forces flying the Hump. Stilwell also planned to use Myitkyina as a bomber base for attacks on the Japanese homeland.

Accompanied by two Chinese divisions, the three battalions of Merrill’s Marauders began its trek through the jungle-choked terrain of Northeast Burma on February 24, 1944. The Marauders quickly struck Japanese outposts all along the Burma front, and by March 3, all battalions had reached the main Japanese line. After four days of harsh fighting, the dug-in Japanese retreated.

The regiment was reduced from its original 3,000 men to fewer than 1,400 and most of those soldiers were sick (jungle diseases), ill-equipped and tired. The men were now looking forward to promised relief and a long rest behind the lines. Stilwell had other ideas.

Assured by the British that the situation in Imphal was under control, Stilwell wanted to launch a final assault to capture Myitkyina. The remaining 1,400 Marauders would spearhead the operation.

On May 17th, 1944, after a grueling 65-mile march over the 6,000-foot Kumon Mountain range (using mules for carrying supplies) to Myitkyina, the Marauders, along with several Chinese regiments, attacked the unsuspecting Japanese at the Myitkyina airfield. Success for the Marauders at the airfield came quickly; however, the town of Myitkyina could not immediately be taken.

Fighting continued throughout the rain-soaked summer. Myitkyina fell on August 3, 1944. The cost was high but the rewards were substantial. A way had been opened for the Ledo (Stilwell) Road. Engineers, laborers, technicians, and construction crews, following closely on the heels of the combat troops, were already clearing ground for highways, gas stations, supply points, and motor shops along the route of the Ledo Road; they were building pipelines to carry aviation fuel directly from India to China.

Despite constant battles with the Japanese, malaria, dysentery and scrub typhus, Merrill’s Marauders fought their way through hundreds of miles of Burmese jungle over seven months.

In five major and thirty minor engagements, they defeated the veteran soldiers of the Japanese 18th Division (conquerors of Singapore and Malaya) who vastly outnumbered them. Always moving to the rear of the main forces of the Japanese, they disrupted enemy supply and communication lines, and climaxed their behind-the-lines operations with the capture of Myitkina, the only all-weather airfield in Burma.

JT