We all know the U. S. Marines used dogs in the Pacific Theater. They were sentries, couriers, and used on patrols to avoid ambush. Despite training to desensitize them to gunfire, many war dogs came away from combat gun-shy. Did any other countries use dogs in combat situations?

As they prepared for D-Day and the fight against Nazi Germany, the 13th Parachute Battalion of the British Army developed a new weapon: parachuting dogs. One heroic hound would even earn a medal for his service.

Brian was a tough paratrooper. He trained hard for his deployment with the British Army during . During his training, he learned how to identify minefields. Then, on the battlefield, he protected his comrades-in-arms – though not all of them made it back. On D-Day, he parachuted under heavy anti-aircraft fire onto the Continent. He was there when the Allies liberated Normandy. A few months before the war’s end, he parachuted into western Germany, from where he marched to the Baltic Sea.

Less than two years after the war, Brian was given an award to recognize his “conspicuous gallantry.” But the bronze medal was not the only thing that distinguished this special soldier from the majority of his comrades: Brian, the tough paratrooper, was a dog, a young Alsatian-Collie mix.

During World War II, the 13th (Lancashire) Parachute Battalion started an adventurous experiment as it prepared for D-Day: enlisting dogs into their ranks. The so-called “paradogs” (short for “parachuting dogs”) were specifically trained to perform tasks such as locating mines, keeping watch and warning about enemies. As a side job, they also served as something of a mascot for the two-legged troops.Finding Heroes among Orphans

Andrew Woolhouse, an amateur historian, surmises that the battalion first got the dog in early 1944 because Lance Cpl. Ken Bailey “had a veterinary background.” Woolhouse researched the battalion for five years and gathered the writings of a number of battalion members from both before and after D-Day to help him write a battalion history, “13 - Lucky for Some: The History of the 13th (Lancashire) Parachute Battalion,” published this year.

At the time, Bailey had been assigned to run the “War Dog Training School” in Hertfordshire. In 1941, the British War Office had made radio appeals for dog-owners to lend their pets to the war effort. This led to the first batch of animals at the training school – though the sheer number of people trying to get rid of their dogs during the war soon made it somewhat of a shelter.

Among these animals was the 2-year-old dog Brian. In Jan. 1944, Bailey wrote in his notebook: “One of the dogs selected from the training school in Hertfordshire was ‘Bing’ a 2 year old Alsatian-Collie cross. Bing had been called Brian by his civilian owner, Betty Fetch, and was the smallest of his litter and due to wartime rationing he was given up.”

In addition to Brian, now called Bing, Bailey took two other dogs into training: Monty and Ranee, both Alsatians (also known as German shepherds). These three would number among Britain’s paradogs during the war, with Ranee being the only female parachuting dog in the war.

Training with Treats

Training began with getting the dogs used to loud noises. At the base in Larkhill Garrison, the dog handlers had the dogs sit for hours on transport aircraft with their propellers spinning. They also trained the dogs to identify the smell of explosives and gunpowder in addition to familiarizing them with possible battlefield scenarios, such as what to do if their master was captured, how to track down enemy soldiers and how to behave during firefights.

Training on the ground lasted roughly two months. But then the dogs started what wasn’t part of the training of the other search dogs in the war: parachuting maneuvers.

The dogs’ slim bodies proved to be advantageous because, during their test jumps, they could use the parachutes that had actually been designed to carry bicycles. In order to make it easier to get the dogs to jump out of the aircraft, they weren’t given anything to drink or eat beforehand. On April 2, 1944, Bailey wrote in his notebook about the first jump with the female Alsatian Ranee. He notes that he carried with him a 2-pound piece of meat, and that the dog sat at his heels eagerly watching as the men at the front of the line jumped out of the plane.

Then it was their time to jump, which Bailey describes in this way:

“After my chute developed, I turned to face the line of flight; the dog was 30 yards away and slightly above. The chute had opened and was oscillating slightly. (Ranee) looked somewhat bewildered but showed no sign of fear. I called out and she immediately turned in my direction and wagged her tail vigorously. The dog touched down 80 feet before I landed. She was completely relaxed, making no attempt to anticipate or resist the landing, rolled over once, scrambled to her feet and stood looking round. I landed 40 feet from her and immediately ran to her, released her and gave her the feed.”

Jump, land, eat: With each training jump, the dogs started enjoying their job more. In fact, the dogs sometimes allowed themselves to be thrown out of the planes or lept out without any coaxing.

Problems with the Plan

Then came the day that the dogs had trained for, D-Day, June 6, 1944: The three planes carrying the members of the 13th Battalion took off at 11:30 p.m. on the previous night and headed for France. At 1:10 a.m., or only 30 seconds behind schedule, the airplanes reached Normandy. Each plane held 20 men and one dog.

Everything seemed to be going according to plan until the hatch was opened. The planes were surrounded by bangs and whizzes, and loud salvos of flak threw yellow light onto the gray clouds.

Bailey and Bing flew on the same airplane and were the last ones in line to jump. But after Bailey boldly sprang out of the hatch, his four-legged pupil turned around and holed up in the back of the aircraft.

In battalion records, it says that the jump master on board, who was responsible for coordinating the jump, was forced to unplug his radio equipment, catch the dog and toss him out of the plane.

What’s more, Bing’s jump reportedly didn’t go as smoothly as his training jumps had: Shortly before setting his four feet on the soil of occupied Europe, Bing was hanging in the branches of the tree his parachute had got caught in. He then had to wait for two hours until his comrades found him with two deep cuts in his face, most likely from German mortar fire.

Honors for the Hound Turned Hero

In what followed, as one soldier in the 13th Battalion later noted, Bing and the other dogs proved to be very useful, especially for locating mines and booby traps. “They would sniff excitedly over it for a few seconds and then sit down looking back at the handler with a quaint mixture of smugness and expectancy,” he wrote, noting that the dogs would then be rewarded with a treat. “The dogs also helped on patrols by sniffing out enemy positions and personnel, hence saving many Allied lives,” he added.

However, in addition to being saviors, the dogs were also victims. Monty was severely wounded on D-Day, while Ranee was separated from her battalion shortly after landing in Normandy and never seen again. But they were later replaced by two German shepherds who had switched sides and soon became friends with Bing.

Bing survived the war and went on to receive the ****en Medal, the UK’s highest honor for animals that have displayed “conspicuous gallantry or devotion to duty while serving with any branch of the Armed Forces or Civil Defence Units.” The medals are awarded by the People’s Dispensary for Sick Animals, a British veterinary charity, and have been bestowed on dogs, pigeons, horses and a cat (for getting rid of rats on a naval ship despite injury).But that was not the last honor for Bing’s service: When he died in 1955, the former paradog was buried in a cemetery of honor for animals northeast of London. Today, one can also find a true-to-life replica of this four-legged hero in the Parachute Regiment and Airborne Forces Museum in Duxford. He is naturally shown wearing his parachute and next to his medal of honor, which bears the words “For Gallantry” and “We Also Serve.”

This article originally appeared in German oneinestages.de, SPIEGEL ONLINE’s history portal. Andrew Woolhouse’s book, “13 - Lucky for Some: The History of the 13th (Lancashire) Parachute Battalion,” is available for purchase on Amazon.

Home front ammunition carriers, Eastern Command UK

http://armyphotos.net/army-soldiers-photos/union-units/#

Faria Valley, New Guinea. 1943-10-20. SX17682 private J. G. Worchester of the 2/27th Australian Infantry Battalion and his dog “Sandy”. “Sandy” was one of the many dogs trained by the United States Dog Detachment for the Australian Army, for use as scouts and messengers for forward patrols. Private Worchester can be seen placing a message in the dog’s collar.

German war dogs

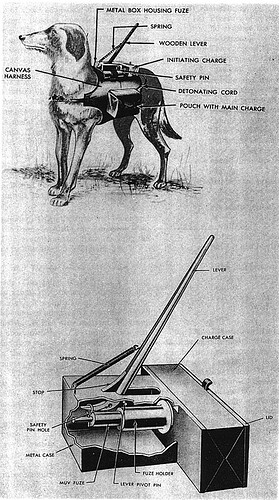

Anti tank mine dogs, trained by a few nations

Marines carry a wounded German shepherd believed to be Caesar to the hospital tent on Bougainville.

The 1st Marine War Dog Platoon was the first war dogs to fight in the War in the Pacific. The platoon was made up of 48 enlisted men that worked in pairs as handlers for 21 Dobermans and three Shepherds. It also included six enlisted instructors and headquarters personnel. They would serve with the 2nd Raider Battalion, under the command of Lt. Clyde A. Henderson.

The Marines under Henderson’s command landed at Bougainville on Nov. 1, 1943. The 24 dogs of the 1st Platoon would wait an hour after the Marines touch down on the beach before following.

The Devil Dogs were met with mixed reactions by other Marines. The idea of using dogs in combat was not yet determined worthwhile by other U.S. Marines. The 1st Marine Dog Platoon was an experimental unit without any standards in place to gauge success. The dogs would truly need to prove their worth across all terrains.

The Devil Dogs of 1st Platoon would quickly show others what made them indispensable. Sentry and messenger dogs had been officially recognized for a while. However on Bougainville, the Devil Dogs were not only in the battle lines, but beyond them in enemy territory as points for patrols.

The Devil Dogs were so efficient in carrying messages, that the Japanese began targeting the dogs by the third day of fighting. The first dog to carry a message through combat would be a Devil Dog named Caesar. Caesar was credited with the delivery of vital information back and forth under heavy fire nine times, and although hit twice, he survived. Another Devil Dog, Jack, was attacked in the jungle, along with one of his handlers. He had received a deep wound in his back, yet was still able to relay the message to his other handler that there had been an attack and stretcher-bearers were needed. With phone lines cut, Jack proved to be essential.

There was one key event that would sway the Marines’ opinion of the Devil Dogs. In the island setting, Marines frequently had to set up camp on beaches. It was a common Japanese tactic to sneak onto the beaches at night, where the Marines camps were set up, and try to kill them in their sleep. Marines continually had to stay alert and they would end up wasting ammunition on an enemy they can’t see. The Doberman’s acute sense of smell, hearing and somewhat nervous energy, gave the dogs the ability to detect the presence of men several hundred yards away. The Devil Dogs were requested by the Marines to join them for a night on the beach. It was a quiet night and the Marines got some sleep. From then on, the Devil Dogs were welcomed by Marines.

The dogs’ helped their handlers dig foxholes, making other Marines jealous. During battle, the dogs would lead infantry points on advances, they were able to explore caves and dugouts safely, as well as scout fortified positions. The dogs can take credit for the security of their units because the Japanese were not able to ambush or infiltrate any units protected by dogs. Sentry duty at night was done occupying foxholes in forward outposts. Hahn’s information shows the dogs and their handlers were officially credited with 350 patrols during final stages of the battles. The handlers accounted for over 300 enemies slain. Only one handler was killed on patrol. Each of the 24 dogs making up 1st Marine Dog Platoon earned the right to be called a Marine.

The 1st War Dog Platoon would play a part in Bougainville, Guam, and Okinawa. The 2nd War Dog Platoon and the 3rd War Dog Platoon would lead their Marines and Devil Dogs throughout Guam, Morotai, Guadalcanal, Aitape, Kwajalein, and Eniwetok. More units would be sent to form the 6th Marine Division which invaded Okinawa. The 1st Marine Brigade would be comprised of units from other platoons, including the 1st War Dog Platoon, invading Guam, along with the 3rd Marine Division and the 77th Army Division.

The first Army War Dog Platoon to enter the Pacific War would be the 25th Quartermaster Corp War Dog Platoon. Led by Lt. Bruce D. Walker, they arrived at Bougainville in early June 1944. Although the Marines had already landed in Bougainville, the 25th Platoon had more scout dogs and they were not met with the heavy fire 1st Platoon did. Their dogs took to caves throughout Bougainville, finding any Japanese trying to hide and secured the island.

Following the 25th Platoon, would be the 26th QMC War Dog Platoon, led by Lt. James Stanley Head. Head was an experienced guide dog trainer. The platoon lands in New Guinea on June 16, 1944, met with prejudice, reluctance to give the dogs a chance, and word of failure. The 26th Platoon proved their value in battle, on Biak Island, July 1, 1944. Later that year, from Sept. 17 to Nov. 10, scout dogs from the 26th Platoon led more than 100 patrols. On the patrols, in the field from one to three days, the dogs never failed to alert at 75 yards or further and there were no casualties when a dog was accompanying. When a dog was leading, scouts were able to move ahead faster with the increased confidence they wouldn’t be ambushed.

The handlers of the 26th Platoon, once doubted, were awarded one Silver Star, eight Bronze Stars, and seven Purple Hearts, two with Oak Leaf clusters. None of their men were killed in action. All members received the prized Combat Infantryman Badge. The platoon also received a unit citation from the 31st Division, and another from the 6th Division.

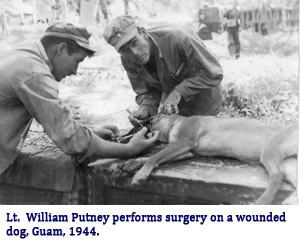

The handlers that worked with the dogs would develop a bond like no other. Handlers watched their dogs put their loyalty before their life, and the love was reciprocated. While medics were available for the Army and Marines, veterinary science was limited. Lt. William Putney, commander of the 3rd War Dog Platoon, was also a veterinarian. Putney would be crucial in developing the care needed for the dogs. He would begin the first sick bay for the dogs where handlers could bring their dogs using stretchers, even though many would just carry them. He was able to perform surgeries and blood transfusions on the dogs injured in combat.

More than 1,000 dogs had trained as Marine Devil Dogs during WWII. Sadly, 29 of these dogs would be listed as killed in action, with 25 of the deaths occurring in Guam. Putney would also play a critical role in helping rehabilitate approximately 550 Devil Dogs, making them able to return to civilian life. In September of 1946, there was no visible war on the horizon and the Marines would end the program. The Devil Dogs would become a part of history.

Between the Marines and the Army, close to 3,000 dogs would return home. Dogs that had owners were offered to come home, but not all wanted them back. After those dogs had been sent home, the government still had a tremendous number of dogs. Legally they would have to sell the dogs to the public by the Treasury Department, but the Army QMC felt that selling dogs used in war to the public without guidelines, rehabilitated or not, may be fall into the wrong hands.

News leaked of the surplus of dogs and the QMC’s opinion on selling the dogs. Once again, Dogs for Defense would rise to action again to help. The War Department gave Dogs for Defense four ways a dog could be placed.

By issue to the Seeing Eye, Inc. as a prospective Seeing Eye dog.

By issue to a military organization as a mascot.

By making available to the dogs’ former handler.

By sale through the Treasury Department.

Applications were screened by Dogs for Defense. Applications from former handlers, veterans, and owners whose dogs were killed in service got first consideration. It was still legally required that any dog sold profit the Treasury Department. The Army and Dogs for Defense decided to charge the recipients of the dogs with the minimum shipping cost, which varied from $14 to $24. In order for the Treasury Department to receive profit, the Army and Dogs for Defense would double the shipping cost and cover the difference.In total, they would receive 17,000 applications that continued into 1947, after the war was over and surplus had run out.

In memory of Capt. Leonard Weinstock

Thanks, good info!

A very good book on Australian tracker dogs in Vietnam is Peter Haran’s ‘Trackers’, which I read several years ago. A lousy job in many respects as the tracker and his dog were allocated to units they had no connection with on an “as needed” basis for specific operations, which could be days or weeks, and then pulled out and reallocated somewhere else, so they were always the strangers in an established infantry unit. A bit like being a permanent FNG in successive units, but a lot more important to the unit. Haran’s dog, Caesar’s, brief history and identity tag are at http://www.awm.gov.au/collection/REL35028/

More on Australian Vietnam war dogs at http://www.anzacday.org.au/history/vietnam/dogs.html

Australian war dogs are included on our Vietnam War nominal roll, which is the official list of all personnel who served in the Vietnam War. http://www.vietnamroll.gov.au/TrackerDogs.aspx

An Australian SAS dog is said to have been captured in Afghanistan, which resulted in an SAS patrol capturing a relevant senior Taliban commander to assist recovery of the dog, after which the SAS sent a message to the Taliban “Can we have our ****ing dog back now?”.

A prisoner exchange duly occurred.

Not formally enlisted but adopted by Australian troops in the Middle East in WWII, Horrie the Wog Dog went through the North African, Greek, Crete and Palestine campaigns. He provided valuable service through his ability to hear approaching aircraft before humans could. Smuggled back to Australia, Horrie lived for several years before quarantine officials found out about him and decided he had to be destroyed. Those officials believed they had destroyed Horrie, but it is generally understood by those with deeper knowledge that a dog of similar appearance was bought from a pound and substituted for Horrie, and that Horrie lived out his life without further interference from government officials.

Fascinating, thanks for sharing that.

I once read somewhere (I tried looking it up but couldn’t find any information) that during WWII, an entire Soviet tank division was forced to retreat because Soviet war dogs with explosives tied to them ran toward Soviet tanks, rather than German tanks.

I think the story has grown in the telling.

There is a thread or posts on this on this site.

Essence was that the Soviets trained dogs to go to tanks with explosives strapped on the dogs, and trigger mechanism on the dog’s back.

In practice, the dogs didn’t distinguish between German and Soviet tanks and became a risk to their own side, so they weren’t used after initial attempts.

Don’t have details from memory, but IIRC it was at nuisance level involving a small number of tanks rather than forcing a division to retreat.

Also, IIRC, a photo of at least one of the dogs looks distinctly like a German Shepherd, which might have been a clue about why it shouldn’t have been used against German tanks. ;)

To fill in a gap in a previous post - the Normand Paratrooper Dog, Bing, was awarded the ****in in Medal, in 1947. The ****in Medal was/is awarded by a British animal charity, The People’s Dispensary for Sick Animals (PDSA) for “conspicuous gallantry or devotion to duty while serving or associated with any branch of the Armed Forces or Civil Defence Units” in the course of an armed conflict. The medal itself is made of dark metal, inscribed with the phrases “For Gallantry” and “We Also Serve” on the obverse. The medal is of sky blue, maroon and green. The ****in Medal has been awarded some 65 times since its inception in 1943. Most of the recipients have been pigeons (communications) and dogs (various military and civil defence duties). There are also some horses, and one cat - Simon, ship’s cat aboard HMS Amethyst, who continued to wage his lone campaign against the ship’s rat infestation in spite of having received battle wounds, and helped to raise morale among the beleaguered crew. Simon, like Bing, survived the war.

As to the Soviet antitank dogs - there seem to be conflicting views as to how much active service these had, but not too much disagreement as to how effective they might have been, which was not very. Their lack of success seems to have been down to three factors. First, the training of the dogs for the battlefield tended to fall short on conditioning them to actual battlefield conditions, causing dogs to run back to their trusted handlers, often with unfortunate results. Secondly, most of the dogs (especially of the early batches) were trained on Soviet (diesel-powered) tanks; because dogs rely on their sense of smell at least as much as on sight, they often failed to recognize German (petrol-powered) tanks as “tanks”, and considered Soviet tanks as targets of preference. Thirdly, German Intelligence quickly realized what was going on, and countered it by spreading the word that all dogs (other than German war dogs) encountered on the Eastern Front had a high probability of carrying rabies - and therefore should be shot on sight as a matter of routine. Not too surprising that so many of the photos of Germans with small animals on the Eastern Front show cats and kittens rather than dogs. A fiasco bad for dogs all round, antitank or not. Best regards, JR.

Bloody Hell ! Apparently, I am not allowed to post the proper name of the in Medal. Does this mean that some Netnanny has a problem with the word "" ? Or with some connotation of “**** In” ? Ridiculous. Reminicent of the early days of Netnannying, when some of the stupid programs blocked the sites of the American Cancer Society because they included the word “breast” … Yours in irritation, JR.

Sometimes one can draw inspiration from knobheads who want a personalised number plate which has already been taken, so they resort to numerals or other symbols.

This would produce the “D1CK1N Medal”.

I agree with your objection to netnanny prissiness. For example, I can’t say I would ***** a balloon or that if I *****ed a balloon it would burst, but on the other side of the body I can’t say *** but, courtesy of American linguistic imperialism, I can say arse.

Imagine how mysterious the King James Bible would be to Americans were this prissiness applied universally in America.

And Jesus, when he had found a young ***, sat thereon

John 12:14

Excellent, RS* - I have never been that good at lateral thinking ! As regards the King James Bible - I suspect that both the politically correct “liberals” and the Bible-thumping “conservatives”, both of whom should favour Net-nannying, would find the task of coming up with an entirely fit-for-purpose Bible Netnanny daunting. One suspects that a lot of innocuous material would be censored, while a fair share of the dirty stuff (especially in the Old Testament) would get through. On one hand, would the lady called “Abishag” survive the Inquisition ? On the other hand, there is Genesis 38, 8-10 -

"8. And Judah said unto Onan [who had married his brother’s widowed wife, Tamar], Go in unto thy brother’s wife, and marry her, and raise up seed to thy brother.

-

And Onan knew that the seed should not be his [i.e. under the current law, any resulting children would be regarded as his deceased brother’s]; and it came to pass, when he went in unto his brother’s wife, that he spilled it on the ground, lest that he should give seed to his brother.

-

And the thing which he did displeased the Lord: wherefore he slew him (also).".

So … Onan married his brother’s widow (dodgy in Louisana, I suspect) but, because he did not want to give rise to children who would be regarded as his brother’s, slept with his wife but used the good old-fashioned (and ineffective) “Withdrawal Method” of contraception (if, indeed, he bothered to get that close to her) and finished by w****ing himself off. And, typically, Jehovah was displeased with the poor guy, and Smote him. Just to make things complete, Onan’s father, Judah, later sleeps with Hamar (who has disguised herself as a harlot), fathering twin boys on her. “Confused ? You won’t be …”

Hmmm … seems a lot dirtier than the poor old ****in Medal - but what would I know ? Actually, there is a fair deal of interesting stuff in this bit of Genesis about family relations, and sheep-shearers and sheep … oh, I’d better stop. Otherwise I might be Smitten, in the truly Biblical sense … Yours from the Ann Summers Tabernacle, JR.

I find this really interesting and I already knew that the axis forces did use dogs for military use but I didn’t know that the allies used dogs. (stupid me)

The net nanny can be troublesome, I was reading about RS*'s youthful pursuits, and found them in Judges 15. And the power of the Lord (or Crown royal) was upon him, and taking up the Jawbone of an *** he (RS*) slew 1,000 Phil***tines. I do find this ***tounding. (should have been 2,000)

hahaa that’s awesome, saving private doge

Genesis ain’t a patch on Leviticus for biblical porn, albeit a bit hard on lepers but useful advice for Onan and his former sister in law but now wife on how to clean up their act with ritual bathing after the spilling of the seed. Leviticus 15, 16-18.

There was an Australian pump company called Onan. I found it highly amusing but, due to biblical ignorance among my countrymen, the joke was lost on everyone else.

Parts are still available if one exhausts the Onan pump which, despite vigorous attempts, I never managed to do with mine. http://onanparts.com/index.php?main_page=index&cPath=1_31

Popular tracts in New Zealand.

Well, in my distant youth I was certainly chasing *** but, alas, had more in common with Onan, but without the woman present or things would have turned out differently. :(:(:(:(

Possibly Australia’s earliest war dog, more or less. A pet, but he was in combat and a POW who escaped, so he qualifies as a war dog.

Nelson, Newfoundland pet dog for the 1st Contingent to the Boer War, lying in front of a bell tent in the Transvaal, two horses in the left distance. His collar has RHA (Royal Horses Artillery) and insignia stamped on it. Nelson was taken with his owner, Private Arthur Edge, with the 1st Contingent in 1899. The Contingent left Port Adelaide for South Africa on 2 November 1889 returning to South Australia on 30 November 1900. On their return Nelson was quarantined from mid-December. In September 1901 Nelson was lent to the National Memorial Committee by Mr G J F Parsons touring the Northern Districts until mid-December 1900 to mid-June 1901. Nelson became the 1st Contingent’s regimental mascot. Lance-Corporal W Rust, a member of the first South Australian Transvaal contingent, wrote: ‘Nelson has been in the thickest of the fighting, and has also experienced the novelty of being a prisoner of war in the hands of the Boers. He was captured on 13 February, but on 5 March escaped. We were on the tramp when he returned. McWilliams, of the West Australians, and our Sergeant Laycock found him returning in the direction of Colesberg, and escorted him back to the company. Needless to relate, Nelson received an ovation from his ‘comrades-in-arms’. We have learnt to love the noble animal, and his absence put a dampener on us all. Our company was offered 50 pounds for Nelson at De Aar, but as money would not buy him, the liberal offer was politely refused. The Colesberg people said the Boers held our pet as a great prize, and decorated him with the colors of the Orange Free State, but he discarded their old rag for the dear old Union Jack. He richly deserves a war medal after displaying such intense loyalty to England’.