Luftwaffe pilot-turned-Canadian performed an act of amazing grace

Ordered into the skies to shoot down a damaged Allied bomber during the Second World War, he could not bring himself to open fire. It would be 43 years before he learned its fate

RAY EAGLE

Special to The Globe and Mail

April 18, 2008

VANCOUVER – Franz Stigler of Surrey, B.C., was a German fighter pilot who committed one of the few documented acts of chivalry during air combat in the Second World War. In 1943, faced with shooting down a badly damaged U.S. bomber whose crew was obviously badly wounded men, he just couldn’t pull the trigger and instead escorted the aircraft to safety.

Within a decade, Mr. Stigler had immigrated to Canada, but for years, he wondered whether the Boeing B-17 had made it back to Britain.

Born in Bavaria when the First World War was at its height, he was meant to be a pilot. His father had served as an observer in the German air force, and after the war, he encouraged his son to take an interest in flying. By the time he was 12, Franz had soloed in a glider.

He studied aeronautical engineering and took flying lessons. After qualifying, he flew several different types of aircraft. In 1939, he joined the fledgling Luftwaffe, and by Sept. 1 he was at war. Despite having flown multiengine aircraft, Mr. Stigler chose to fly fighters. On most of his combat missions, he flew the legendary Messerschmitt BF-109F, which, according to fighter pilots on both sides, had characteristics that were superior to the equally legendary Supermarine Spitfire and Hawker Hurricane. Like most fighter pilots, he flew with several different squadrons and eventually commanded two, 8/11 and 12/IV Squadrons (or Jagdstaffels), which in turn were part of Jagdgeschwader 27, the equivalent of an Allied fighter wing.

In four years of operational flying, he served in North Africa, Sicily, Italy, Holland and Germany. He was shot down 17 times and bailed out of aircraft four times, but otherwise managed to land or crash-land. His score was 28 confirmed aircraft shot down or badly damaged and more than 30 “probables.” He flew a total of 417 combat missions from 1940 to 1945 and earned the Iron Cross Second Class, the Iron Cross First Class and the German Cross in Gold.

Although there were many German pilots with much higher scores, some claiming well in excess of a 100, it is doubtful that they survived as many critical situations. Mr. Stigler was wounded four times, suffered burns and sustained lifelong scars on his legs and head, among them a very visible forehead mark made by a bullet that came though the windshield of his fighter. Fortunately, the windshield slowed the bullet’s velocity and it failed to penetrate his skull.

While stationed in the Mediterranean, his squadron was detailed to escort Stuka dive bombers targeting a shipping convoy. Each Me-109 carried a 225-kilogram bomb slung underneath and, having reached the target, they were instructed to dive and release the bomb as they pulled out. The idea was to make the bomb “skip” on the water and hit the ship’s side. Mr. Stigler released his bomb and it bounced so well that it became airborne and kept pace just off his port wing. He climbed away as fast as he could.

By late 1943, he was posted in Holland at a base from where the Luftwaffe could best attack Allied aircraft on both the outward and return legs of bombing missions. The British and Canadians flew the four-engined Avro Lancasters and Short Sterlings, while the mainstay of the U.S. Army Air Force was the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress.

One of the Flying Fortresses was piloted by a 22-year-old lieutenant named Charlie Brown, from Western, W.V. On Dec. 20, 1943, Mr. Brown took off from his base at Kimbolton, near Cambridge, as part of a raid on the Focke-Wulf fighter plant at Bremen in Germany. It was only his second combat mission, and his first as captain. His B-17, with its equally young crew, had the whimsical name of “Ye Olde Pub.” The plane reached the target without incident, dropped its bomb load and turned for home, only to suffer a direct hit from an anti-aircraft gun. The Plexiglass nose was shattered and two of the four engines were damaged. Unable to maintain his position within the formation, Mr. Brown dropped astern.

Eight German fighters appeared and pounced in an attack that damaged a third engine, destroyed most of the tail and knocked out the oxygen, hydraulic and electrical systems. The controls were only partly responsive, the rear gunner was dead and three other crew members were wounded. To make matters worse, Mr. Brown had been struck in the shoulder by flak.

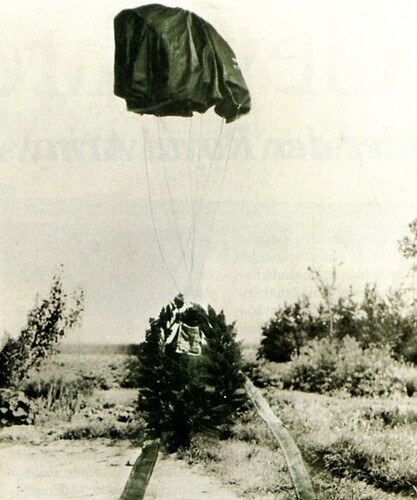

Only half-conscious because of a lack of oxygen, he lost control and the plane inverted and spiralled down to within about 100 metres of the ground. Miraculously, he came to his senses and levelled out. He struggled to gain height and speed, but with only one engine at full power and one at half power, the aircraft was close to stalling. Three of his crew were unable to bail out, so his only options were to crash-land in enemy territory or try to make it back to England.

While struggling with the controls, he became aware of a lone Me-109 flying alongside. The B-17 had lumbered through the skies near a German airbase and the fighter had been sent up to finish it off. The German pilot circled around the B-17, came back to his original position and pointed towards the ground. Mr. Brown, still dazed, ignored the suggestion that he should attempt to land, and kept flying. The enemy pilot held position until the B-17 was over the North Sea and pointed in the direction of England. He waved, saluted and flew back toward to Holland.

Mr. Brown and his crew made it back to England and landed safely at Seething in Norfolk. The story of the encounter was immediately classified as secret, as it would not have gone over well for the public to know of a chivalrous enemy when they were exhorted to hate all Germans.

The pilot was Franz Stigler. When he closed on the bomber, preparing to shoot it down, he was astonished.

“I was amazed that the aircraft could fly,” he told The Associated Press in 1997. “The B-17 is the most respected airplane. I flew within 12 yards. It was a wreck. The tail gunner was lying in blood … holes all over.”

The pilot, he noticed was also wounded and “his crew was running all up and down tending the wounded.”

Mr. Stigler held his fire. He could not bring himself to attack a plane carrying dead and severely wounded crew. “It would be like shooting at a man in parachute,” he said years later.

Back at base, he reported that he had successfully shot down the B-17 and that it had crashed into the sea. To admit the truth would have risked court-martial and very likely execution. “I couldn’t tell anyone about it at home that I had let them go or I would have been looking down the barrels of a firing squad,” he said.

Earlier in the day, he had already downed two other B-17s, and a third would have assured him the coveted Knight’s Cross medal.

In 1953, Mr. Stigler emigrated to Canada - first to Montreal and then to British Columbia. He found work as a mechanic with a logging company in the Queen Charlotte Islands and later settled in Surrey, where he became operations manager for the truck division of Hertz. He than ran his own trucking company for several years, assisted by his wife, Hija.

Through the years, he never forgot the damaged B-17. He often mentioned the plane to Hija, and speculated about what had happened to the crew. For all he knew, it might have crashed into the sea on its own.

For 43 years, the riddle went unanswered and then a letter appeared in a newsletter for German fighter pilots, past and present. Charlie Brown, the American pilot, had submitted it on a hunch.

Mr. Brown had survived the war and remained in the U.S. Air force and served various staff roles before retiring as a lieutenant colonel. By 1986, he had settled in Florida and sometimes he thought about the enemy pilot who had given his crew a chance at survival. It was not until he attended a convention of the U.S. Air Force Association that year that a chance remark by a friend prompted him to act. He wrote to the newsletter, seeking information and describing the extraordinary 1943 incident over the North Sea.

Two months went by and finally a letter with a Canadian stamp arrived. The writer said his name was Franz Stigler, and that he was the pilot who had waved the B-17 on to England.

In the summer of 1990, the two men finally met at a hotel in Seattle. It was the first opportunity they had to pin down a time and place. A friendship immediately resulted, and eventually they toured together to tell their story at reunions and at special museum events. Not surprisingly, they found themselves celebrities among veterans and became the subjects of many articles in newspapers. Peter Gzowski, host of CBC’s Morningside, was the first to interview them on radio.

For his part, Mr. Brown also found an unexpected release. In the long years since the war, he had suffered a recurring nightmare in which he was in an aircraft spiralling down toward trees and buildings. The dreams ceased the day he met Franz Stigler.

Once enemies, the two men became as close as brothers and talked on the phone almost every week. “For some reason, we really hit it off,” Mr. Brown said.

FRANZ STIGLER

Franz Stigler was born Aug. 21, 1915, in Regensburg, Germany. He died March 22, 2008, in Surrey, B.C., of complications from surgery. He was 92. He is survived by wife Hija and daughter Jovita. Two earlier marriages ended in divorce. He is also survived by Charlie Brown of Perrine, Fla.

Source: http://www.airlinepilotforums.com/hangar-talk/25639-chivalry-air-when-enemy-became-friend.html

There’s actually an article on wikipedia telling about it.

There’s actually an article on wikipedia telling about it.