“Bravest of the Brave” - On 18 June, 1815, Wellington’s army - mainly composed of British, allied German and Netherlands units - stood on the defense at Waterloo. Of the British forces, a recent history has estimated that some 40 per cent of the British troops were Irish. As with the rest of the soldiers engaged at Waterloo, the bulk of the British were recent recruits with little or no training. Britain’s main reserve of veterans (from the Peninsula) had been sent on a clean-up operation in the Caribbean. Not all, however, were so ill-prepared.

“Bravest of the Brave” - On 18 June, 1815, Wellington’s army - mainly composed of British, allied German and Netherlands units - stood on the defense at Waterloo. Of the British forces, a recent history has estimated that some 40 per cent of the British troops were Irish. As with the rest of the soldiers engaged at Waterloo, the bulk of the British were recent recruits with little or no training. Britain’s main reserve of veterans (from the Peninsula) had been sent on a clean-up operation in the Caribbean. Not all, however, were so ill-prepared.

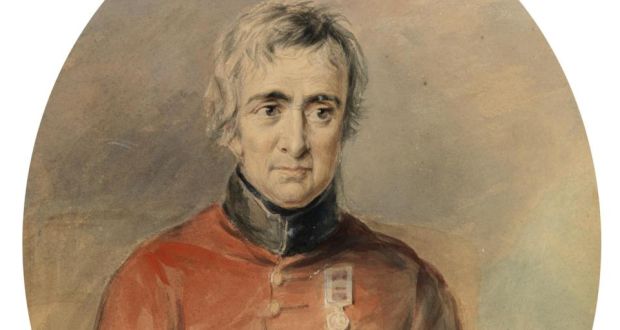

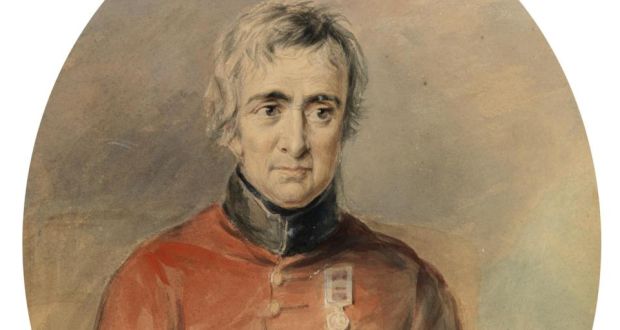

Roman Catholic soldiers had service in the British forces opened to them by a “Catholic Relief Act” of, I think, the 1780s, initiating Ireland’s role as a major source of British recruits through the 18th and 19th centuries. One man take advantage of this relief was James Graham, of Clones, Co. Monaghan. He enlisted in the Coldstream Guards, and was a well-trained (if not very combat-experienced) professional soldier by the time of Waterloo.

Wellington’s line at Waterloo was anchored, at either end, by the occupied walled farmhouses of La Haye Sainte (east) and Hougoumont (west). Wellington judged the holding of these locations as vital. Consequently, La Haye Sainte was manned by an élite unit of sharpshooters from the King’s German Legion, and Hougoumont by Coldstream Guards, supported by infantry from a nearby sunken road.

As the battle developed, an increasingly heavy and violent attack on the Hougoumont farmyard evolved. Why this came about is still a matter of debate among historians. Some argue that Hougoumont was side-show - a “battle within a battle”, that developed mainly because Napoléon had shifted his position behind the lines in such a way that he had a disproportionately prominent view of the extreme right of the Allied line. Wellington does not appear to have believed this; he heavily reinforced British infantry in the adjacent sunken road in response to French attacks. Napoléon seems to have shared his opinion that Hougoumont was one of the keys to the battlefield. It is worth noting that, if the French had broken through the Allies’ right flank, they could have cut them off from their line of retreat to the sea - recognized as one of the Emperor’s pre-battle objectives.

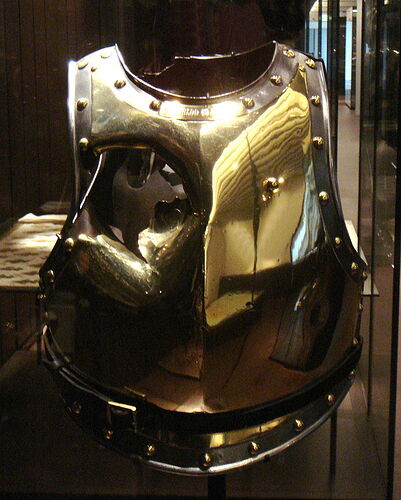

The crisis in the Hougoumont battle came when a gate of the farmhouse, left open (or more likely inadequately barricaded) in order to facilitate communication and supply from the sunken road) was assaulted by French sappers and broken open. Anything up to 100 French soldiers entered the walled farmyard, attacking British troops inside. However, behind them, the Coldstreamers’ commanding officer, Lt. Colonel James McDonnell determined to get the gate closed before complete disaster ensued. He was assisted, spontaneously, by a number of officers and men of the Guards, including James Graham, his brother, and a number of other ranks. In spite of severe pressure, Graham and his little crew succeeded in pressing the gate closed. Cpl. James Graham was the man who bolted the gate, which was then barricaded. The French who had entered the farmyard were killed to the last man, only a young drummer boy being spared. Later in the day, as the French continued to attack and climb over the wall, James Graham saved the life of an officer by shooting down a French sharpshooter aiming to shoot the officer, and rescued his brother from a burning barn (the brother subsequently died of his wounds).

The Duke of Wellington later wrote that the “closing of the gate at Hugoumont” was the key event of the battle. McDonnell and James Graham were celebrated, the latter (by Wellington) as the bravest man at Waterloo. Graham was honoured, in addition to the Waterloo Medal, with a special Medal for Bravery. He continued in service after the war, notably taking part in the suppression of the “Cato Street Conspiracy” against the Crown. In the course of the attendant riot, Graham is credited with saving the life of another officer - Frederick FitzClarence, an illegitimate son of King William IV.

James Graham continued in service up to 1830, at which time he was discharged, in effect, due to disability and age. He was consigned to residence in the Royal Hospital, Kilmainham, Dublin (equivalent of London’s Royal Hospital, Chelsea), where he died in 1845, and rests still. With best regards and great respect, JR.

Portrait of James Graham, above, is a painting on panel, author unknown, in the collection of the National Gallery of Ireland. JR.

“Bravest of the Brave” - On 18 June, 1815, Wellington’s army - mainly composed of British, allied German and Netherlands units - stood on the defense at Waterloo. Of the British forces, a recent history has estimated that some 40 per cent of the British troops were Irish. As with the rest of the soldiers engaged at Waterloo, the bulk of the British were recent recruits with little or no training. Britain’s main reserve of veterans (from the Peninsula) had been sent on a clean-up operation in the Caribbean. Not all, however, were so ill-prepared.

“Bravest of the Brave” - On 18 June, 1815, Wellington’s army - mainly composed of British, allied German and Netherlands units - stood on the defense at Waterloo. Of the British forces, a recent history has estimated that some 40 per cent of the British troops were Irish. As with the rest of the soldiers engaged at Waterloo, the bulk of the British were recent recruits with little or no training. Britain’s main reserve of veterans (from the Peninsula) had been sent on a clean-up operation in the Caribbean. Not all, however, were so ill-prepared.