We were to give as much time as possible for the main defencive positions to be prepared and manned, for defence in depth to be done. 50 missile Regt with its Lance were always ready to drop on us if we failed in a bridge dem.

That would certainly have been an incentive to get it done quickly, talk about the boss over your shoulder… The one bridge we did have to cross if it were still standing when we got to it, was a light ,and narrow thing rated for 20 tons. We would have to move one at a time, very slowly with one track up on the sidewalk.

Nice.

Enemy waits for first tank to almost complete crossing and then destroys it, blocking bridge and trapping remaining tanks, assuming enemy hasn’t previously destroyed bridge.

What was the drill then? Stand and fight to the death; scatter and try to find another crossing; or abandon tanks? (I’m guessing that the drill didn’t go past the first option.)

It’s revealing what you and leccy have said.

Down here, we were preparing in that 1960s-1980s era for small wars / jungle wars which were essentially infantry wars with conventional weapons with a high prospect of survival for most combatants, as was the case in Vietnam.

Until your and leccy’s posts, I didn’t realise just how massively and rapidly destructive WWIII in Europe was expected to be.

What was the ultimate expectation? That the Warsaw Pact steamroller produces a new Dunkirk; the Pact forces are held somewhere in Europe; or they’re defeated?

Whichever, it sounds like the civilians in western Europe were in for a worse time across more ground than WWI and WWII.

I’m not arguing that OKW was “moral” or necessarily legal in every endeavor. However, there is little doubt that the resentment caused spitefulness of the Versailles Treaty certainly created a situation that Hitler was able to exploit. Many of the General Staff were not pro-Hitler, but they certainly were not Francophiles either…

In all due respect, how do we know how the Rhineland plebiscite was conducted and under what conditions? Granted, I have not studied the issue, but if the Rhineland plebiscite was conducted like the Saar’s plebiscite a year earlier, I would suggest that that referendum is not a valid or fair measure of support.

It’s mentioned in Tooze’s “Wages” but it has been a while since I have read about it. From what I remember, any dissent of anti-Nazi German-speakers in the Rhineland was certainly quashed but there is little doubt that the residents overwhelmingly wanted to rejoin Germany. Again, its occupation at various points - often conducted heavy-handedly by the French - was a cause of resentment and bitterness…

But I doubt Hitler would have known this information, or believed it, in 1940. Hitler used the “false neutrals” phrase to Ribbentrop and others in order to describe countries he was quite willing to invade on the false assumption that those countries were, in fact, helping Germany’s enemies and could not be trusted to support the Axis. The situation you accurately described above might easily fit the chaotic situation of the “Little Entente” countries in the 1920s, who could not agree to form a common defense against Germany (although I assume France wanted the Little Entente to work because she had hoped to curtail German expansion in the East).

Yes well, Germany was going in rationalize the invasions of it neighbors by any logic it needed. And Belgium was going to play an important part in the attack in any case, even with the emphasis being in the Sedan. Also, Hitler may have been aware that the French wanted a secure Netherlands as they ultimately hoped to use the Low Countries for an eventual invasion route into Germany…

Forgive me. I did not know this. In the 1970s, I remember having a conversation with a gentleman from the French Army at the dinner table. We were discussing World War II, and eventually, we started to discuss the so-called “phoney war.” He remembers watching the German army rehearsing military maneuvers at the Maginot Line through a set of binoculars. I asked him, “Well, you were at war with the Germans, why didn’t you shoot at them?” He said, “They did not shoot at us, so we thought it convenient that we not shoot at them.” At the time, I thought it a peculiar way of thinking, but, of course, I didn’t know what I know now.

.

Interesting, I’ve read that they often would do things such as hang their washing in the open with little fear of sniper fire. There were some desultory clashes of patrols I understand, but certainly the period of waiting was far more caustic for the French Army as they did little more than build forts and do agricultural labor in many cases as the Heer trained and reequipped itself…

I wasn’t around at the time, but my understanding was that nobody expected the nukes to stay grounded for more than about 48 hours or so. Once the tactical nukes in Germany start flying, everything else would fly and then we’d all be crispy critters.

I do apologize, as I often write in tangents about history because I have no one to talk to about these things. My friends are all buried or have perished at the hands of the Germans and Russians, and those that are still alive to have remembered those times are thousands of miles away from the shores of America. (Thank the Lord for the Internet!)

Now on to the subject. I remember reading an interesting book called, “Tapping Hitler’s Generals.” I found this book enjoyable because, for the first time, Hitler’s Generals are speaking candidly about the war situation and Hitler’s military commanding abilities without the Gestapo or political police listening in on the conversation. I particularly found General Thoma’s observations fascinating reading; Thoma, of course, was captured by the British in North Africa in 1942, and he professed that the war was over for the Axis the minute France fell but no one in the General Staff had the audacity to stand up to Hitler at the end of 1940 or since. “Ninety-nine percent of them are spineless creatures,” He said of the General Staff, “They’ve always been ‘yes’ men. They’ve never been commanders, but only assistants of the Commander.” He goes on to say: “The Kaiser was as gentle as a nun in comparison to Adolf Hitler. The former did at least let you speak your mind–the latter won’t let you open your mouth…None of my superiors has the right to order me to do [Hitler’s] dirty work, let him do it himself. I’ve said so straight out. I can swear a solemn oath that not a single man has been shot by my people.” And: “I remember that last spring in the conferences with HQ, the army commanders were there and they told us about conversations they had had with the Fuhrer, ‘The Fuhrer is personally firmly convinced that the country in Europe which is nearest to communism is England. He said that last year [1941].’ That’s complete madness, that’s a sign that the man has never been out in the world.”

I think you are right about the General Staff, and Hitler’s willingness to exploit the raw emotions of these commanders who had seen Germany’s defeat. But it is indeed interesting how he cleverly promoted lebensraum as not just an abstract political theory written by a Pan-German nationalist but of military necessity, thus intertwining the political with the military, arguably disproving what the General Staff insistently declared at the Nuremberg Trials (Keitel and Jodl still believed that what they had done was strictly military and, therefore, as military men, had no interest in the political aspects of the regime they had served).

But, I don’t believe that the General Staff whole-hardheartedly supported war. There is too much evidence to support the hypothesis that most of the Staff thought that Germany did not possess enough raw materials to wage a war of attrition, which Hitler’s lebensraum suggested. It seems safe to say that Hitler visualized a war without an end and probably wouldn’t tolerate peace with the eastern Slavs for longer than a year. I don’t know, Nicholas, if you’ve read George Orwell, but the situation here calls out similarities with his book, 1984. If my memory serves me well, one can equate Nazi Germany to Oceania, which is in a constant state of war with Eurasia or Eastasia. (Goebbels would be proud of Orwell’s Ministries of Peace and Truth.) Anyway, I thought that the General Staff believed that French POWs should be treated with respect, while the OKW had less interest in treating Russian, Polish, Italian, or Ukrainian POWs honorably, although, I am aware of only one complaint made about the treatment of Polish and Russian POWs. Historian Richard Evans once said that some of the General Staff spoke French even though she was a constant thorn in Germany’s side.

I think that was the case with the Saar Plebiscite, although in the case of the Saar, the referendum didn’t provoke much international protest, despite League of Nation’s protest at the heavy-handed behavior of the Nazis. I keep forgetting to read Adam Tooze’s book, although I should. I am still slogging my way through Clay Blair’s esoteric “Hitler’s U-Boat War.”

Sometimes I believe that Hitler didn’t know himself why he had started the war. I’m often reminded of a quote from Joachim Fest’s book, “Inside Hitler’s Bunker,” where Ribbentrop states that Hitler said to him, and I’m paraphrasing here, that he didn’t want to negotiate peace with the Russians because he would end up breaking his promise in the end, and that he couldn’t help himself in that regard.

My French friend believed that the High Command was largely to blame during that period. He said that when he would write his reports, he knew that most of what he would write would end up in the trashcan or worse, heavily criticized by his Superiors for the wrong reasons.

That is the text book move when dealing with a Column formation, especially if one has the opportunity to catch them on a bridge, or a causeway, or even a city street. There is no room to disperse, and maneuver. Hit the leading element, the rearmost element, and then you can pick the rest apart as you please. Normally, we would have Brigade level recon units, and air cover watching out ahead of the column to be sure that the bridge was still there, and not a trap. We kept in mind that Warsaw might use airborne troops, but were mostly concerned with their air force taking down the bridge preemptively.

If the recon said the bridge was there, across we would go at walking speed, a 52 ton Tank on a 20 ton bridge. If it was out, then hopefully, those in charge of alternatives would head us toward the secondary crossing point. (if there was one.) the idea being in all of this to not engage any such forces if it was possible to go around them.(unless ordered to do so.) The mission was to take our positions at the Fulda Gap, and Delay, and reduce Warsaw forces should they begin to come through.

The contemporary wisdom was that Warsaw had minimally, a 3 to 1 advantage in Armor, and possibly as much as 5 to 1. In reality it was probably less than 3 to 1 even including their marginally serviceable tanks, and the scads of light BMP’s and PT-76 vehicles, which could not withstand the M-2 50 BMG. Warsaw preferred mass armored formations for invasion, and while armor, and gun technology was pretty much even between us, NATO had superior fire control, and communications. This would allow us to engage them at ranges much greater than they were able to answer. It was hoped that this advantage, along with Artillery,TOW missiles, and air support, (assuming there was any left) the massed formations could be ground down, and stopped. Planners worked from the worst case point of view which is why the tactical nuclear weapons were so well integrated, even our 8inch howitzers had Nuclear ordnance. Although I’m sure that there were several different yields on the shelf, we knew mostly of the .5 kiloton device. If it looked like Warsaw was going to break out of the Gap, they were then to be used. And I concur with PDF that if the tactical stuff started going, then the larger stuff would follow soon enough. Part of this idea was to punch them in the face so hard, that they would stop to reconsider their plan. (the moment of pause) If they stood down, then the city killers might stay in their holes. But there was no guarantee of that, its just what we were told. All of those decisions could/would be made within the first 48 hrs.

My knowledge of the war plans at the time would agree with you RS in that they intended to roll over the NATO delaying forces stationed in Europe, and going as far as they could, and at the least be too entrenched for the follow up forces to dislodge easily. A second Dunkirk would doubtless have pleased them greatly. The ultimate plan was to contain, and destroy them in the approach ways, then successively delay any surviving units should there be any still able, or interested in continuing.(it was said that if you lived through the first minute of an engagement you were likely to survive it altogether) There were 3 avenues of approach for the Warsaw Pact, Fulda was the one we had to cover. The much advertised Neutron warhead that came along later, was intended to lethally irradiate the enemy formations while causing much less blast damage. I’m just really happy that Dr. Strangelove, and Failsafe were as close as humanity ever came to all of that. (I’m wearing my Capt. Midnight anti radiation tinfoil hat as I type this…) Sweet dreams all…

I think maybe towards the end with the generation of NATO ‘super’ tanks, there was a thought that NATO could hold (without nukes) and even turn the tables on the Warsaw through counter offensives using mobility and vastly superior fire control and survivability…

Around the time you were doing your tank commanding I was in what might have been equivalent to your recon unit, which was called an assault troop (variously configured but about the equivalent of an infantry platoon, except fewer in number and mechanised in APCs = M113, although we rarely had an M113 as they were mostly in Vietnam or training the troops who were going there,) in our armoured corps.

As armoured corps, but cavalry (and that’s generous for grunts delivered by any vehicle which happened to be available) rather than armour, our primary function was to go ahead of whatever was more important coming down the road behind us and identify, report back on, or clear threats such as ambushes, road blocks, bridges set to detonate, etc.

What was coming down the road behind us was presumed for our corps to be tanks, which have a strong dislike of going into places where they could be ambushed, road blocked, or on bridges which detonate etc, but in practice could be any unit which wanted a path cleared.

We weren’t exactly expendable in the sense of being put forward to no purpose, but just better to lose than seriously useful battlefield assets like tanks. Or artillery. Or even trucks.

We followed the standard tactic for such units in all armies of being pushed out on foot anywhere between about 50 metres and, rarely, ½ to 1 kilometre ahead of whatever was thought to be more important behind us.

However, we were also trained in various Vietnam era infantry tactics such as patrolling, ambushing, and cordon and search. And a bit of search and destroy.

But, unlike you and leccy, nobody told us that most of us weren’t going to make it past the first 48 hours. It seems we were training for and tens of thousands were involved in a real war in Vietnam where, statistically, very few got killed or badly hurt although raw numbers are that many did, while you and leccy were training for a possible war with unimaginably worse casualties but nobody ended up getting killed or badly hurt.

Which leads to the paradoxical conclusion that several hundred thousand combatants, and perhaps an equal or greater number of civilians, died in Vietnam which ended up as a communist victory, yet nobody died in Europe in a potentially vastly worse war which ended up, without a shot being fired, in defeat of the Soviet and aligned communists.

Are wars of mutually assured destruction better, as long as they don’t happen, when backed by economic and other sanctions and greater military production / capacity by the winner which overwhelm the loser, than real wars?

Not unlike one of our officers who, upon our column coming to an old timber bridge in the middle of nowhere with a sign stating its maximum load was about 20% of the Saracens we were in, duly inspected it on the basis of his deep knowledge and experience as a tax department clerk or something equally irrelevant in civilian life (my troop officer was a junior pharmacist and, as an officer, was probably a very good pharmacist), pronounced it safe to cross. Naturally, the officer stood in a suitably impressive military pose outside the Saracens watching the crossing while those aboard hoped the Saracens didn’t plunge into the creek below, because it’s hard enough to get out of a Saracen with SLRs and in full kit with everyone inside cooperating when it’s upright and, I expect, ****ing near impossible when it’s upside down under water and panic takes hold.

The problem with tanks on the battlefield is that, at least when they’re in support of infantry and given that infantry takes the ground that matters, tanks are a bit like capital ships on the ocean pre-aircraft carriers which can do massive damage to lesser forces but are too valuable to expose to the risk of loss, so they tend to be held back once there is any sign of a serious threat to them or, in many cases, just uncertainty about whether there is a serious threat, with a protective screen around them.

I take it from your description of your tank unit’s function that it wasn’t the sort of mobile infantry support role I was trained in (without tanks, as most of them were in Vietnam) but more of part of a massed, and potentially sacrificial, defence in an overall plan to delay the enemy’s advance.

By the late 1980’s, some military analysts were saying that NATO had a 1.2-to-1 advantage in armor when all factors such as optics, gun power (the 120mm Rheinmetall gun), vastly superior armor on the new M-1’s and Leopards, and mobility were factored in…

…

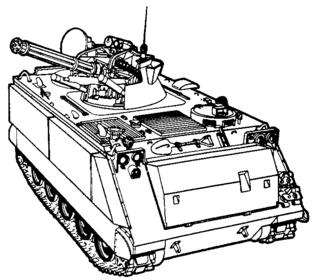

I think the Aussies get some of the credit for adapting the first ad hoc Infantry Fighting Vehicles (IFV’s) by converting the M-113’s from battle taxis to an AFV with real teeth and organic firepower. The South Vietnamese also get a bit of credit I think.

…

Not unlike one of our officers who, upon our column coming to an old timber bridge in the middle of nowhere with a sign stating its maximum load was about 20% of the Saracens we were in, duly inspected it on the basis of his deep knowledge and experience as a tax department clerk or something equally irrelevant in civilian life (my troop officer was a junior pharmacist and, as an officer, was probably a very good pharmacist), pronounced it safe to cross. Naturally, the officer stood in a suitably impressive military pose outside the Saracens watching the crossing while those aboard hoped the Saracens didn’t plunge into the creek below, because it’s hard enough to get out of a Saracen with SLRs and in full kit with everyone inside cooperating when it’s upright and, I expect, ****ing near impossible when it’s upside down under water and panic takes hold.

What an arsehole! At least evacuate the Saracens of all but a driver and have everyone else walk across…

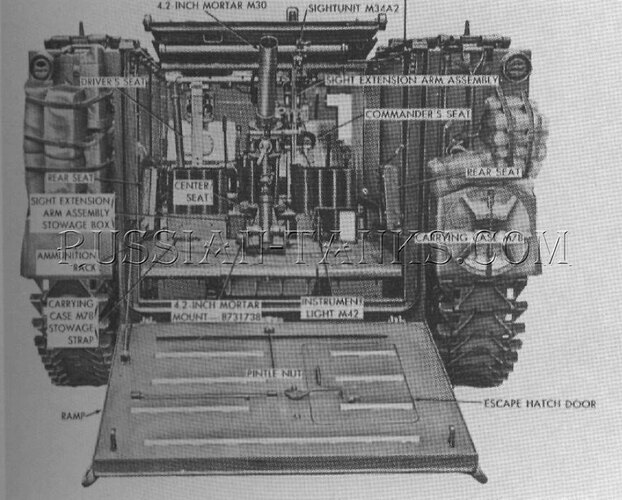

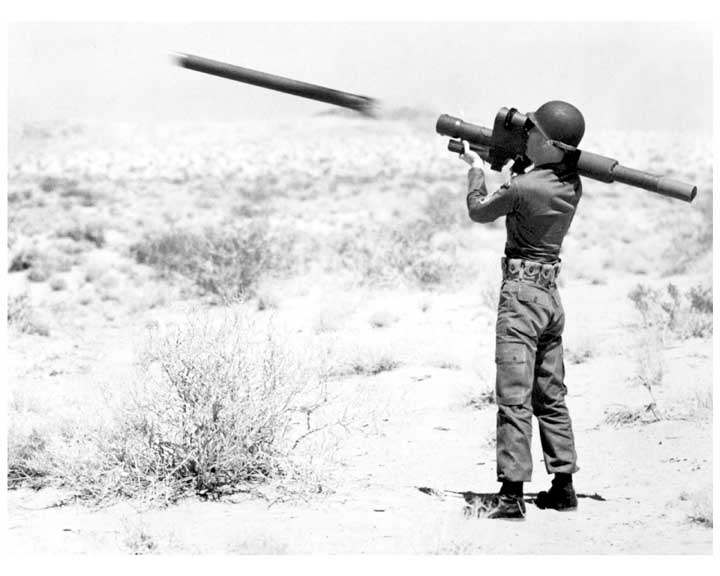

Our Recon forces had some teeth to them if a fight was called for, Their principal vehicle was the M-114 Track, which carried as its primary weapon an automatic 20 mm gun. It fired a “bridge mix” of A.P. and explosive ammo. This was deemed enough to cause trouble for the enemy, and still provide a fast exit for the recon boys. The M-113 APC was also pretty versatile, lending itself to many different roles. One a Command track, another as medical track. Then there was the “A-Cav” version which had two .30 cal machine guns positions, and one .50 BMG position, all with plate armor protection. Then the Mortar track having a 4.2 inch mortar which could be operated from either inside, or outside the vehicle. A very handy addition to the Recon Track and its gun. There was also a version that had a 20mm Vulcan with Radar for A.A. 1st pic, M-114 recon. 2nd bad manual pic of the M-113 mortar track. 3rd, the 20mm Vulcan A.A. track.

We made them a lot more survivable than the American APC’s by field welding belly plates to them to resist mines, and running ours on diesel rather then the much more flammable petrol the Americans ran.

Or better yet, order the guys in the back out and ride there himself - that or stand underneath the bridge.

Which vehicles were you using? the 113’s we used were aluminum hulled, and burned diesel, the M-59 it replaced was steel hulled, and used gas. The recon M-114 also ran on gas.

I was sent to school for the 113, 2 weeks learning the details of maintenance mostly, but driving, and swimming them as well. Although I graduated with the highest scores, I was also voted most likely to sink my own track while swimming it. :mrgreen:

RS*: "The problem with tanks on the battlefield is that, at least when they’re in support of infantry and given that infantry takes the ground that matters, tanks are a bit like capital ships on the ocean pre-aircraft carriers which can do massive damage to lesser forces but are too valuable to expose to the risk of loss, so they tend to be held back once there is any sign of a serious threat to them or, in many cases, just uncertainty about whether there is a serious threat, with a protective screen around them.

I take it from your description of your tank unit’s function that it wasn’t the sort of mobile infantry support role I was trained in (without tanks, as most of them were in Vietnam) but more of part of a massed, and potentially sacrificial, defence in an overall plan to delay the enemy’s advance. "

The plan did include infantry, all of which was mechanized and driven around in the lovely M-113 There was also a fair amount of Cavalry both Armored, and Air. The only parts of the Cav units that we would be likely to have along were those having M-551 Sheridan tanks. their Tow missiles would be handy in the open, and if it was woodsy, they could always go to the regular munitions (while not very fast, their 152mm HE would be nice to have around ) It would be a bad idea to have these light little tanks moving out in the open as they had very little protection. Better to keep them in the tree lines, or defilade positions like snipers. The missiles would be very useful ranging past 3,000 meters, but the caseless, really a combustible case conventional ammo made for slow work.

At any rate, as far as we were trained for this particular adventure, the infantry would remain out of the way as we would operate as Tanks only, hiding behind whatever features we had, or could make, and engage the enemy formations at the extremes of our ability (for the M-60 series that was 4.4 km.) this was all poke and hope, as no one had ever been trained to fire from that range. ( you might miss your intended target but hit another nearby.) At ranges nearer to 2,500 meters, the system was pretty good, and hits were 70% sure. If we could keep about 2,000 meters between us, and them, that would allow us to retain the initiative. This supposedly would force the Soviets to disperse, take up a fighting formation, and proceed more slowly. This could take some time as soviet line tanks did not have radios,only the platoon leaders, company commanders did, so everything had to be communicated by hand signals, or flags and this only after going up, and back down the centralized command system. While they were doing all of that, we would move back by alternating bounds maintaining fire as much as possible, along with whatever Gun, and rocket artillery was delivering. and maybe some air support, maybe. We would do this as many times as we could, slow them, take some out, and move to do it again. If it became clear that we were on the short end, or were destroyed, like the stand of the 300 at Thermopylae, that is when the little nukes would be let off the leash . We did not consider ourselves in any way as hard to chew as the Spartans were, but we would do our share.

If for some reason we had orders to close with the enemy, then the infantry would come forward in their aluminum chariots to help protect us, and exploit any opportunities to further reduce the evil Empire’s numbers. The Cav guys would attempt to make flank attacks to sow confusion, and distraction. Well around our whole formation, would be the Red Eye teams, 4 of them at their compass point positions to help knock down Migs, and Helos that came to rain on our parade. In the big scheme, we were considered completely expendable to keep the Red army out of Western Europe. (Hopefully, Chuck Norris would get there before that happened, and make the World safe for Democracy ) included, a pic of a Red Eye launcher.

As a Sapper with CRA CF my sections particular operating area for the initial day was the Harz mountains, we had the simple job of blowing and mining everything we could, just complete route denial. If left alive and by some miracle able to rejoin our Squadron we would revert back to 33 Armd Bde in 4 Armd Div (as always happened in exercise after the obligatory 6 hours dead).

Not too many knew that every bridge, ferry crossing, narrow defile road between hills or mountains was pre-prepared for demolition.

Explosives for each were kept nearby in the quantity and type required along with the actual demolition plan for where to place them. Brackets on bridges so charges slotted straight in, measleshafts in which “cheese’s” were lowered down (40-150lb charges that looked like a wheel of cheese) on abbutments, in roads, defiles, ferry landing pads.

Steel beams in holes in the ground that could be pulled up and locked in place, concrete blocks on sides of road to drop on them (sounds so similar to what the British did in 1940 onwards).

As the covering force we just blew everything to slow them down, the recce reported strength and direction, infantry provided cover for us and small units of point defence ‘hit and run in 432 :/’, the plan was designed to make parts of the assault slow while others could advance at fast speed and then be caught in the flanks and dealt with by overwhelming firepower, the Warsaw Pact forces having no back up from their flanks.

One of the main reserves counted on was the French placing their military under Nato Command for operations. Britain itself only had one full Division in reserve (2nd Inf) in UK along with the TA and Reservists called up to flesh out the existing Divs (1st, 3rd and 4th Armd in Germany) and provide most of the rear area support and defence. Nato flanks were the responsibility of the Commando Brigade (A)MFL UK - (ACE) Allied Command Europe, Mobile Force and the Airlanding brigade based around the Paras.

Bearing in mind that, with the following exception, we weren’t permanently using any M113s as most them were being used by real soldiers, apart from a command M113 (in which I spent a few lonely hours one night jammed against the ramp as the lowest of the low and found that its principal function was to provide a dry crib for sergeants looking at pictures in stick - i.e. porn - books while officers were up the front - i.e. a few feet away - doing officery things, which was probably looking at upmarket stick books and, unlike the sergeants, possibly reading the articles.).

The original M113s were petrol engined and built until 1964. I expect that a fair number of these were in Vietnam with US forces in the mid to late 60s which is the period I had in mind with the reference to US M113s having petrol engines. As far as I’m aware, all Australian delivered M113s followed the switch to diesel in 1964. My understanding of US M113s in Vietnam being petrol engined and inclined to brew up is based on information from Australian soldiers serving there from the mid 60s.

You have PM.

[Australian] M113 Armoured Personnel Carriers

Designed and built in the United States in the late 1950s, the M113 was introduced into service with the US military in 1960. The improved, diesel powered M113A1 was purchased in 1964 by the Australian government and the first vehicles began to arrive in Australia in 1965. The M113A1 has been employed by a variety of units, including armoured and infantry. This vehicle type has been used operationally in South Vietnam, Somalia, Rwanda, and East Timor.

The first Australian APCs to arrive in South Vietnam were from 1 APC Troop, a reduced troop of ten M113A1 APCs from A Squadron, 4th/19th Prince of Wales’s Light Horse Regiment, which arrived at Vung Tau on 8 June 1965. Initially armed with an M2HB .50-calibre machine-gun, the M113A1 was soon fitted with a protective armour shield to provide protection for the otherwise exposed crew commander. The shields proved to be of limited value, and in the second half of 1966 some of the APCs deployed to South Vietnam were modified by fitting Model 74C command cupolas, made by Aircraft Armaments Incorporated. Only 20 Model 74C cupolas were purchased, of which 19 were sent to South Vietnam.

Permanent improvements were made with the introduction of the Cadillac Gage T-50 (Aust) turret, which could be fitted with either a .50 calibre machine-gun and .30 calibre machine-gun combination, making the vehicle an LRV, or twin .30 calibre machine-guns in the APC. Only the APC and LRV variants were fitted with the turret: all other variants within the family of vehicles retained the flex-mounted commanders machine-gun. By the end of the Vietnam commitment, or soon afterwards, the armament on the APC/LRV was standardised with a .50/.30 combination.

The M113AS3 upgraded the M113A1 with a new engine, drive train, brakes, increased ballistic protection, external fuel tanks, modified stowage, and many other modifications. The M113AS4 (APC/LRV) upgrade lengthened the vehicle and an additional pair of road wheels were added. A new single-person turret armed with an M2HB Quick Change Barrel machine-gun was also added.

Specifications

M113A1 Armoured Personnel Carrier (APC)

Armament: .50 calibre and .30 calibre machine-guns

Armour: 12–38 mm

Crew: 2 + 10 passengers

Power plant: GMC V6 diesel

Speed (max.): 66 km/h

Length: 4.87 m

Height: 2.41 m

Width: 2.69 m

Weight: 10.5 t

Apparently he was well regarded as an officer, at least by other officers.

His custom made or customised uniforms certainly gave the strutting little **** a certain distinction, as did his ‘press on’ attitude, as with the Saracen episode.

That’s about as much as know about him. A captain was only marginally more remote to me than a colonel (I believe my unit had one) or a field marshal (my country didn’t have one) for grunts like me.